LET us say that you, as a taxpayer, were called upon to pay for every fraudulent share of oil-well and gold-mine stock sold to credulous investors in this country. Let us suppose, in addition, that you were held liable for the injuries suffered by every person whose chair was pulled from under him by a nitwit prankster.

You'd raise hell, and demand that Something Be Done!

Well, you're paying for something even less enchanting: the daily cost of running to ground every phony clue concerning the purely idiotic and wholly nonexistent “flying saucers.”

Pranksters, half-wits, cranks, publicity hounds, and fanatics in general are having the time of their lives playing on the gullibility and Cold War jitters of the average citizen. It is their malicious fancy to populate the skies over America with a vessel that just does not exist — the flying saucer. And every time a newspaper or radio news bureau falls for their gag, or dementia, another legion of screwballs is mobilized. Many of the daft stories they circulate must be investigated.

Now and then the lunatic fringe in America, who could see whales in the sky if whale-seeing became the Thing To Do, gains unwarranted reassurance from respected quarters. A usually conservative radio commentator swears that there are flying saucers and that they are secret Navy aircraft. The conservative David Lawrence, of the U.S. News & World Report, solemnly assures his readers that flying saucers exist. True Magazine prints two widely quoted articles, one by Donald Keyhoe, one-time aeronautical adviser to the Department of Commerce, and the other by a Navy commander and radar expert, testifying to the existence of such craft. Airmen (and airwomen) employed and trusted by such commercial air lines as TWA, Eastern, United, and Chicago and Southern, speak of unidentifiable winged things blazing by their ships. And Frank Scully, a Hollywood humorist whose most substantial literary effort up to that time was something called Fun in Bed, writes a best seller in which a mysterious “Dr. Gee” tells of grounded saucers complete with tiny men from the planet Venus. And so on.

The “saucer department” of the United States Air Force, an unhappy facet of the important Air Materiel Command at Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio, feels dutybound to investigate not only the claims and warnings of responsible people but also the vagrant dreams and downright hoaxes of less respected folks.

All of this has cost you an appalling amount of money since that hapless Tuesday, June 24, 1947, when a Boise, Idaho, businessman named Kenneth Arnold announced (for publication, unfortunately) that while steering his private plane around Washington's Mt. Rainier he had spotted a chain of nine saucerlike objects playing tag with the jagged peaks at “fantastic speed.”

Americans as far back as Thomas Jefferson had been reporting, usually apologetically, seeing what they considered nonastronomical bodies floating or sizzling in their skies. But Arnold's report ignited a chain reaction of mass hypnotism and fraud that has taken on the guise of a prolonged “Martian Invasion” broadcast by that bizarre hambone, Orson Welles.

The ink was barely dry on Arnold's report about his apparition (he estimated that the nine bright things he saw were about twenty-five miles away, traveling at 1,200 mph) before others in this country began seeing flying “hubcaps,” “dimes,” “tear drops,” “ice-cream cones,” “pie plates,” “saucers,” and “disks.”

From under what amounted to every old rock in the country emerged True Believers, and gagsters who, seeing a royal chance for what they considered fun, began operations. They were promptly joined by the envious. The neighbor of a man who got his name in the newspapers as one who saw a flying saucer coveted his notoriety and, in a short time, was trying to top him by spotting a team of saucers. It was (and is) an easy achievement to see a saucer once the mind is made up.

You can see a heavenly host of flying saucers simply by looking a bit too long at a bright sun and then looking to another part of the sky. Red corpuscles, flitting past the retina of the eye, supply the mirage. It helps, too, to begin with a touch of dyspepsia.

The nonsense of flying saucers would be as harmless as the legend of Kilroy's omnipresence if it were not an integral part of the Air Force's credo to maintain a lively interest in whatever is reported in the American skies. That's its job and, with heavy heart, it feels it cannot afford to pigeonhole any saucer report. It has sent agents from its Office of Special Investigation and enlisted the aid of the FBI on missions improbable enough to wrest a snort of derision from an editor of Weird Comics.

For instance, it looked into the report of a man and wife who wrote in to say that while on a hiking trip through a woods, they had detected a flying saucer “moving about” in a clump of tall, thick pines. It developed, after considerable questioning by agents who had traveled hundreds of miles to hear the story, that the couple estimated they were two or three miles away from the “saucer” and that impenetrable woods were between them and what they thought they saw.

In another case, an Ohio farmer excitedly called Air Materiel Command to give a vivid description of “two huge saucers” that had raced out of the stratosphere, hovered over two small islands in a lake near his home, lowered sixteen steel claws, scooped up samples of earth, and sped away. Agents found out that the man had been released from an insane asylum two weeks before his hallucination.

SOMETIMES many months are needed to complete the investigation of a preposterous flying-saucer story.

Late in 1949, at the nineteenth hole of Hollywood's Lakeside Country Club, film actor Bruce Cabot overheard a man named Si Newton say he knew a man who had in his possession parts of a flying saucer. The friend-of-the-friend spoke also of a “magnetic radio” taken from a grounded saucer, which had been exhibiting miraculous powers as an oil-divining rod. Cabot reported the incident to an Air Force office in Los Angeles, which relayed the tip to Wright Field, and the mechanism of an investigation began to turn.

Cabot went on location and could not be reached. Newton was vaguely known at Lakeside, but the club couldn't put the investigators in touch with him. The trails cooled, but the investigation expense remained hot, until January 6, 1950, when the Kansas City Times printed an interview with one Rudy Fick, giving somewhat similar details.

Fick was found and said he had seen none of these wonders but had been told about them by someone he called “Coulter.” He didn't know Coulter's first name or where to reach him, but he understood he was a friend of Jack Murphy, of the Ford Company in Denver.

When the highly skeptical Murphy was questioned, “Coulter” became George Koehler, an advertising salesman for a Denver radio station. Most of the fantastic stories that Murphy had heard attribµted to Koehler, had come to Murphy, he said, through a mutual friend named Morley B. Davies, of a foremost advertising agency.

Probing deeper and deeper into the maze, the investigators heard from one of the principals that he understood that parts of two grounded saucers were being held in the “United States Research Bureau” in Los Angeles. The Post Office Department's inspectors reported that there was no such place.

There now entered into the case a mysterious “Dr. Gebauer” (or Jarbrauer) from whom Koehler was said to have borrowed the “magnetic radio.” He entered in name only. The Doc, as we will call him in a vain effort to simplify, was the fount of most of the stories that swirled through the case. He had been a party to many supernatural adventures, and was said to have supplied Koehler with souvenirs from a grounded saucer — several small gears and metal disks and a gadget said to be a radio that picked up occasional messages in a language not of this earth.

Murphy had seen the souvenirs, he said, and had identified the disks as standard “knockout plugs” of the kind placed in the walls of automobile engines to help prevent cracks caused by freezing. The gears were stenciled with an Arabic numeral and an arrow, but were otherwise standard. The radio, if it was one, was as silent as a clam when Murphy saw it.

Yet the story expanded. Investigators were told that Koehler had quoted the Doc as saying he (the Doc) and another “scientist” had lifted one of the grounded saucers from the place where it had crashed, but that they had hastily dropped it when it showed signs of taking off.

Investigators heard, too, that one of the saucers — said to have alighted near Aztec, New Mexico — had contained sixteen men ranging in height from thirtysix to forty-two inches. The Doc and eight other “magnetic scientists” alleged to have been called in by the Air Force were detailed to lift the charred bodies of the midgets out of the saucer (“which had a beam of 99-99/l00ths feet”) and examine them. Later, when another and smaller saucer “fell near Phoenix,” the Doc helped to take out the crew of two little men and was quoted as saying that these, like the previous sixteen, had come from Venus. Fifteen others had parachuted to earth and “had made themselves invisible” when the Doc gave chase.

One can perhaps picture the facial expressions of the sane and sober investigators when Davies quoted Koehler as saying that he had either seen or heard that the grounded saucers came from Venus at a speed of 100,000 miles per second. And that he (Koehler) had examined a saucer in the Doc's alleged laboratory near Phoenix, after slipping into a special one-piece examining suit that proved to be an insufficient precaution because, as he entered the place, a warning bell sounded “on account of the plate in his head.”

During the bizarre inquiry, the fantastic material of which was so soon to be presented in straight-faced book form by Frank Scully, investigators had to track down a report that one of the little men had been sent to Chicago's “Rosenwald Institution,” for examination. The directors of the famed Rosenwald Foundation issued an immediate and indignant denial.

For nearly six months, Air Force officers and trained civilian agents — who had been schooled for more rewarding work at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars — were immobilized on this preposterous case, which ended with several of the principals refusing to answer investigators' questions on “Constitutional grounds.”

And nothing can be done about it!

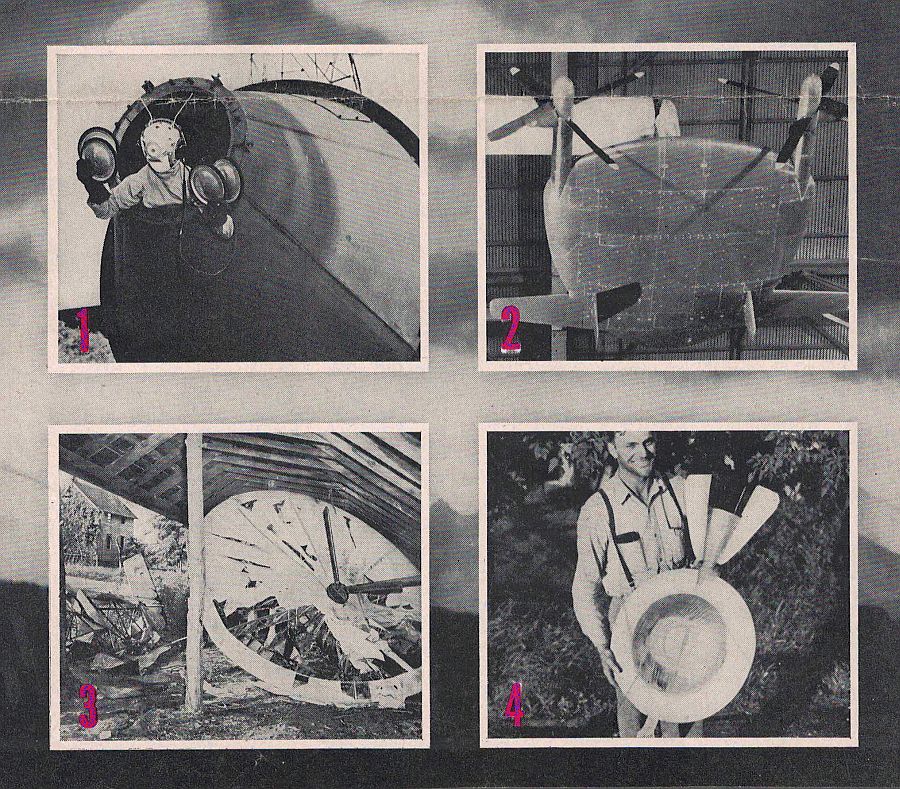

ON June 19, 1950, the Air Materiel Command received a letter from one Martin W. Peterson. Enclosed were four snapshots of a friend holding an odd object with a saucerlike body. From its thin sides, there protruded what appeared to be the tip of a spear and the fins and exhaust-pipe assembly of a miniature V-2.

Peterson was located in Warren, Minnesota. So was his friend, the saucer man — Walter Sirek, a gas-station attendant. Sirek told the investigators that he had found the strange device two years before, imbedded in the earth behind Nish’s Tavern, in Warren. He had figured, he said, that it was the work of a local tinsmith named Art Jensen. Jensen, when questioned, remembered putting something of the sort together at the request of a Warren hardware man named Ted Heyen and a radio repairman named Robert Schaeffer — as a gag entry in a local newspaper “saucer contest.” An acetylene torch had been played over the tail surfaces to give them the appearance of having been scorched by gases escaping from the hauntingly familiar “engine” encased in the saucer.

Heyen and Schaeffer tired of their gadget after a time and threw it away. Sirek found it. Peterson, visiting Sirek shortly thereafter, took snapshots of Sirek holding the contraption — and two years later sent them to the Air Materiel Command.

It took this particular investigative chain reaction from June nineteenth to September twenty-seventh to run its course. Agents had to be transported from Wright Field, Washington, and elsewhere to the points of inquiry, fed, housed, and paid. The fruits of their labors were a few apologies and the saucer — which had been made of the lid of an automatic washing machine, a sawed-off curtain-rod spear, tin tail assembly, and an “engine” composed of a disemboweled midget radio and an old insecticide bomb.

More malicious gagsters have taken the trouble to buy and crudely assemble mounds of scrap steel and iron, burn the junk into an unrecognizable tangle, and report to the Air Force that a saucer had crashed and burned on their property. However plain the hoax, the Air Force often feels that it must take samples of the “wreckage” for study in its Wright Field laboratories or in other metallurgical centers.

And nothing can be done about such frauds. A man who pilfers a three-cent stamp from the Post Office Department can be fined and sent to a Federal prison. One who turns in a false alarm that routs out the local fire department on a Halloween night can also be jailed, as can a man who writes a check for a dollar when he has no bank funds to cover it. Yet the most callous and cynical saucerhoaxers will continue to go scot free, with a cackle of delight, until a penal act is created to check such offenses.

There can, of course, be honest mistakes. Not even the Air Materiel Command is safe from authentic-looking mirages. Last year a radar operator at Wright Field picked up a curiously shaped object on his screen, shortly after a near-by farmer had phoned the field to report a saucer headed that way. Visual observation was not possible at the field because black smoke from the chimneys of a cement plant had settled over the area.

Jets were dispatched to chase the object. As they neared it — obscure in the smoke haze but of a vaguely different color — the radio compasses on the instrument boards of the pursuing Air Force planes spun around as if they had just passed over a radio guide beacon.

It was a magnetically charged cloud, a familiar phenomenon of the heavens and one that is always able to jar a plane’s radio compass and reveal itself on a radar screen.

At 11:30 A.M. last August fifteenth, Nick Mariana, manager of the Great Falls, Montana, baseball club, looked up from the grandstand of the ball park and saw what he later described as two bright flying saucers, streaking across the clear Montana sky. He raced outside the park, unlocked his car, took out his home-movie camera, ran back to the stands, adjusted the camera and exposed about fifteen feet of film, aiming at that part of the sky where he had seen his saucers. He panned the camera from left to right.

The Air Force came into the case, received the film, enlarged it many times, and — sure enough — the film showed two bright disks that appeared to be streaking across the sky.

After some study, the Air Force was able to tell Mariana that the bright disks on his film were sun reflections from the ball park’s water tower. And when he insisted that he had seen two bright things blazing across the sky, the Air Force agreed. It had checked with the operations officer of the Great Falls air-base and found that two F-84’s (Air Force jets with a top speed of 600 mph) had landed at the near-by field at 11:33 A.M.

THERE have been many cases in which the Air Force drew criticism, wholly unjustified, because it could give no pat explanation of what seemed phenomenal events.

The True Believers in flying saucers, as well as those who seem to have taken up saucers commercially, like to point to the strange death of Capt. Thomas F. Mantell, Jr.

On the afternoon of January 7, 1948, the combat veteran was leading a wedge of three F-51's to Louisville when he was asked by the control tower at Godman airbase, near Fort Knox, to investigate a report that a mysterious round object, “250 feet in diameter and giving off a reddish glow,” was in the air over the great gold cache.

Mantell and his buddies gave chase up to 18,000 feet, at which point two of the three '51's peeled off and dropped down to Godman. They had no oxygen equipment — nor did Mantell, who radioed back that he had spotted something “tremendous and metallic” above him and would pursue it up to 20,000, the limit of his unaided lung power.

That was the last message from Mantell. He and his plane were found a short time later near Fort Knox, the wreckage strewn over a half-mile area.

DONALD F. Keyhoe, writing in True Magazine some time later, rejected Air Force theories concerning Mantell's death and quoted one of the F-51 pilots as saying: “It looks like a coverup to me. I think Mantell did just what he said he would — closed in on the thing. I think he either collided with it, or more likely they knocked him out of the air. They'd think he was trying to bring them down, barging in like that.” “They” were not further identified.

The Air Force's first diagnosis was that Mantell probably was chasing one of those large, silvery meteorological balloons used in the continuing studies of cosmic rays and, in following it too high, fell unconscious or dead from lack of oxygen.

A second Air Force proposal was that the airman had been deluded by a rare daytime appearance of Venus and, in the chase, had been suffocated by the rare air high above the earth. Air Force critics leaped on what they considered an evasive job of answering and, as a result, fifteen months after Mantell's death, the Air Force acknowledged honestly, “The mysterious object that the flier chased to his death is still unidentified.”

Keyhoe contended in his article that in view of the fact that the wreckage of Mantell's plane had been scattered over an area of a half mile it obviously had “disintegrated in mid-air.”

If it had done so, the Air Force wearily answered, the plane's wreckage would have spread itself over a much greater stretch of land. A B-29 went to pieces at 30,000 feet not long ago, and its debris covered a twenty-mile area.

The Air Force has had to close its saucer files (which are marked “Confidential” only because no purpose could be served by revealing the names of FBI agents and its own investigators from the Office of Special Investigation) on cases other than the tragic Mantell incident. Two such cases concerned an Eastern Air Lines DC-3 and an Air National Guard F-51.

The Eastern crew reported at 2:45 A.M., July 24, 1948 (an hour after a “flaming object” was observed over Robbins Field, Macon, Georgia), that a big, wingless thing that glowed as if from a magnesium flare had shot past the DC-3 near Montgomery, Alabama. The plane's pilot, Clarence S. Chiles, former Air Transport Command man, and co-pilot, John B. Whitted, B-29 pilot during the war, agreed that the thing had a fiery plume of a tail and, after passing the air liner, zoomed up into the overcast at about 700 mph - “its jet or prop wash rocking our DC-3.”

National Guard Lt. George F. Gorman described, the following October first, a “dog fight” he had waged in the night over Fargo, North Dakota, with a noiseless little light that appeared to be the exhaust glow from a supernatural craft easily capable of outmaneuvering the maneuverable F-51.

The Air Force knocks down the testimony of experienced airmen with regret. It speaks of weather balloons, flares, fireballs, meteorites, hallucinations, pilot fatigue, and that ephemeral thing called the power of suggestion. It points out, too, that the windshields and windows of some air liners tend to reflect and distort ground lights, and that for a while the windshields of early F-51’s were accidentally built in such a way as to cause a pilot to believe occasionally that he was seeing parts of the landscape floating in the air above him.

THE HEAVY, costly job of tracking down and disproving an average of five saucer scares a day has fallen into the patient lap of an outstanding Air Force colonel named Harold E. Watson. Watson climaxed this writer’s investigation of the flying-saucer delusion and hoax by flying in from Wright Field to Washington to lay his files before me at the Pentagon.

“I’ve seen a lot of flying saucers,” the heavily decorated and prematurely gray airman told me, with a note of weary resignation in his voice. “Chased them and caught them, too,” he added. “And every single saucer turned out to be the sun or moon shining off the wing or body of a plane — the DC-4 at 12,000 feet or more is an especial offender — or a weather balloon, or sun reflections, or something else readily explainable.” Watson attributed the occasional rises in saucer-observation reports to periodical national broadcasts, scarehead magazine and newspaper articles and, last fall, to Scully’s Behind the Flying Saucers, a book that became a best seller but that, said Watson, the authority, “made me slightly ill after fifteen pages.” Watson added, “The most ridiculous part of the whole nonsense is the spreading report that the Air Force is trying to keep something sinister from the people. We are accused of having in our possession the bodies of ‘little men’ from Venus, grounded saucers from outer space and from Russia, and secret saucers of our own make.”

He shook his head, sadly. “I wish we did have a form of propulsion capable of doing all the things people attribute to saucers. It certainly would have come in handy during the war in Korea.”

I asked him why he remained in command of “Project Saucer,” a Wright Field unit the Air Force announced it was formally disbanding December 27, 1949.

“We’re still in business,” he replied, “and will stay in it as long as people insist on reporting invasions of the skies we command. But we are now able to eliminate a great number of reports. We look into only such reports as appear to be outside the spheres of regular reports we receive on scheduled and unscheduled flights of commercial and military aircraft, radar and astrological reports, balloon releases, rocket and guided-missile tests, and air-gunnery targets towed by mother planes or remotely controlled. This sort of screening reduces the number of cases that seem to warrant investigation to about five a day.

“And at the end of a great percentage of these five, we find a crackpot or some joker who thinks it’s real funny to cause us trouble and expense.

“Try to get this over to the people,” he asked. “There are no flying saucers, no ‘little men,’ no burned saucer wreckage or pieces of flying saucers, no disappearing parachutists, no potential enemy with any craft of this sort, and none of our own design.

“There just ain't no such animal, but tracking down the nonexistent cause of mass hysteria is still costing us — and you — plenty.”

THE END

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|