I suppose that I should be especially well qualified to write about flying saucers since I happen to be one of the few persons who has actually seen one.

My solar studies take me frequently to Colorado and New Mexico, and I was at the Holloman Air Base, near Alamogordo, N. M., at the height of the flying-saucer scare. That very morning, I had glimpsed what seemed to be several saucers moving overhead — until I focused my eyes more clearly and recognized the objects as weather balloons. That afternoon, I expressed my belief that most of the saucers could be thus explained. But others in the group — including several well-known scientists — indicated that there was probably more to the saucer story than that.

Early that evening, I had my second attack of saucers. I was in the back seat of an automobile, being driven toward Alamogordo and admiring the full moon as it rose over Sacramento Peak toward the east. A few degrees' north of the moon, I noticed what seemed to be a bright star, and then a second star not far from the first. Casually, I assumed that they were Castor and Pollux in the constellation of Gemini. Then, very suddenly, I realized that Gemini was a winter object; the two stars had to be something else.

Like most astronomers, I am always hopeful of finding a nova (exploding star) which can be seen with the naked eye, so I rapidly opened the window of the car for a better look. I could bring neither of these objects into clear focus, although nearby Antares was sharp. Both hazy disks shone with a slightly bluish light. They were, in a sense, “flying” simply because they were elevated. Suddenly, alive to the fact that I was seeing something unusual, I asked the driver to stop. We climbed out of the car just in time to see the saucers literally fade away as mysteriously as they had appeared. I reported the occurrence in detail to the Air Force.

I later found that an English meteorologist, Edward J. Lowe, had recorded a similar phenomenon as long ago as 1838 — similar except for the fact he saw four instead of two ghostly images flying near the moon.

Perhaps you expect me to say, at this point, that I can explain exactly what I saw that evening. I am sorry to disappoint you. I cannot. I have certain ideas on the subject, but they are only hypotheses — reasonable but not yet fully confirmed.

I shall explain those ideas, but first let me say what I do NOT believe. I do NOT believe that what I saw, or anything anyone has reported seeing, were missiles or messengers or vehicles from the moon or Mars or space. I do NOT believe they were missiles or messengers or vehicles from Russia or any other foreign country.

Indeed, how simple science and life would be if every time we encountered some seemingly inexplicable fact, we could blame it on some outside force over which we have no control. Such a mode of thought is as old as man himself. Our prehistoric ancestors personalized all the forces of nature. Gods blew the winds, threw lightning bolts and stoked the fires that belch forth from volcanic craters.

Brilliant showers of meteors have made men fear that the end of the world was imminent. The ancients have interpreted a solar eclipse as a dragon devouring the sun and rejoiced when their beating drums and weapons frightened the dragon away.

How simple this type of science. No laboratory experiment to prove or test the hypotheses. No complicated mathematics to study the details of the process. For each new and unexplained fact, we invent a new god — or assume the existence of a superintelligence.

How simple — and how wrong!

Centuries of civilization have taught us the futility of inventing mysterious forces and superhuman beings. You could explain anything that way. Such explanations, however, are completely useless and nature falls into chaos, subject to the whim of a pagan deity instead of to the orderly processes of natural laws.

As a scientist, I am not bothered if I cannot give a complete, iron-clad explanation for every phenomenon I meet. Unraveling the puzzles of science is my business — as well as my pleasure. I find the world still full of unsolved problems. I look for the explanations, but I do not arbitrarily invent forces that make explanation unnecessary.

Why, then, have so many civilized people chosen to adopt an uncivilized attitude toward flying saucers? I think there are three reasons:

First, flying saucers are unusual. All of us are used to regularity. We naturally attribute mystery to the unusual.

Second, we are all nervous. We live in a world that has suddenly become hostile. We have unleashed forces we cannot control; many persons fear we are heading toward a war that will end in the destruction of civilization.

Third, people enjoy being frightened a little. They go to Boris Karloff double features.

But such analysis should concern the psychologist rather than the natural scientist, so let me hasten back to our flying saucers.

First of all, we must recognize that “flying saucers,” in the public mind, cover a wide variety of objects and phenomena. Some of them, we can almost immediately dispose of, although the mere fact of their misinterpretation has been one of the chief difficulties men have encountered in getting at the basic truth.

A man sitting in the park on a calm summer afternoon scarcely realizes how intense the winds aloft may be. Perhaps real gales exist, with speeds in excess of 60 miles an hour, different layers moving in opposite directions. Light, flat objects such as newspapers or kites can be caught in an occasional whirlwind and lifted to enormous heights, where they may fly for hundreds of miles before they again reach the ground. Weather balloons, which are often released in groups rather than singly, are not at all uncommon. Indeed, most such objects lose their true identity when viewed against the sky. And it is extremely hard to recognize them.

Occasional reflections from distant planes or even from the backs of high-flying birds account for some of the reports. The planet Venus has, on many occasions, produced its own series of sensations. Few people seem to realize that this planet, when at greatest brilliance, can be plainly seen in the daytime. If floating cirrus clouds overlie it, the planet may give the illusion of being in rapid motion. Most people find it difficult to focus their eyes on a distant object; hence, they see a bright blur in the sky and thus give rise to another flying-saucer story.

But by no means all of the objects can be so dismissed. After we have eliminated the false saucers and the erroneous reports that we trace to misidentification, there do remain a number that we cannot completely write off. Such as the ones I saw myself.

The first question we are called upon to answer is this: If these objects are natural objects, why did they suddenly appear for the first time in 1947? An honest question and a basic one; for if it cannot be answered, we are in difficulties. But the answer is simple: They were seen in the skies long before 1947. Scientific literature is full of them.

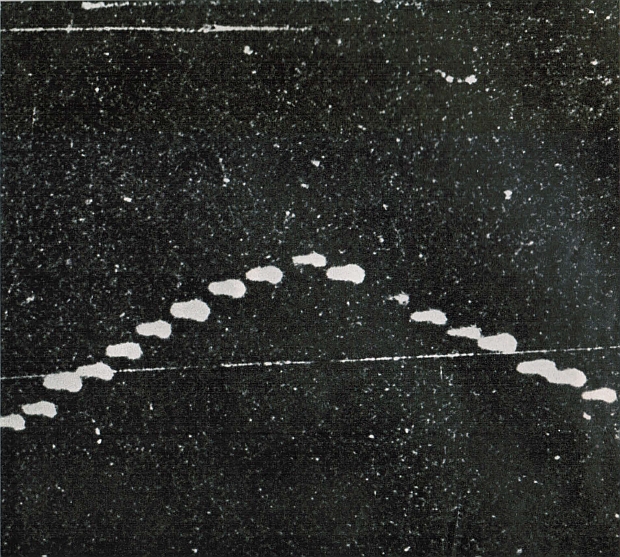

Take, for example, the Lubbock Lights, which appeared in the sky near Lubbock, Texas, last summer and were photographed. Similar phenomena have been long reported. England was mildly excited over the Durham Lights almost a century ago.

In 1897, our papers were filled with stories about a mysterious cigar-shaped airship seen at odd places over the country. The lights and men aboard were clearly visible. Finally, the great inventor Thomas A. Edison himself disposed of the rumor.

Here is a quotation from the magazine Nature for May 25, 1893: “During a recent wintry cruise in H.M.S. Caroline, a curious phenomenon was seen.... Unusual lights were reported by the officer of the watch. They appeared sometimes as a mass, at others spread out in an irregular line. They bore north until I lost sight of them about midnight.... The globes of fire altered in their formation... now in a massed group with an outlying light, then the isolated one would disappear and the others would take the form of a crescent of diamonds.”

The account also mentioned a “looming mirage,” of which I shall have more to say later. This report interests me for two reasons: First, it would almost serve as a description of the Lubbock Lights. Second, my own theory of the Lubbock Lights was developed, and tested in my laboratory, before I found this account in Nature — and my theory directly associates looming mirages with the lights.

The next question is quite natural: Even granting that these phenomena have a long history, why are they so much more frequent today than in the past?

List the places where flying saucers have been seen, and you will notice that the great majority were reported in very hot areas, over deserts — in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. For years, these states were sparsely settled.

But since the war began, they are the areas in which the most startling population growth has been tallied. Irrigation has brought farmers in. The dry heat has made tourist havens of Phoenix and Tucson. The air age has made these flat, clear-skied areas the natural locations for great bomber and fighter bases. Finally, atomic energy has chosen New Mexico as its headquarters.

In brief, there are more eyes to scan the heavens. Hence, more is seen. The answer is as simple as that. The clear skies are themselves a partial answer. Beyond two or three miles, especially toward the horizon, the milky haze cuts down visibility in Eastern areas. In the West, one is accustomed to seeing a mountain peak more than 150 miles away.

Finally, the most important question of all: If the saucers aren’t superhuman or controlled by superhumans, what are they?

First, we must study the reports.

A careful analysis of all the available data indicates that — after we have subtracted the balloons, papers, distant planes, Venus and the like — a substantial amount of reliable but unexplained material still remains. This falls into several definite patterns: ovals, disks or other patterns, either shining silver by day or luminous by night. They may appear singly, in clusters or fly in precise geometrical formation. The best-defined patterns of this type have been called the Lubbock Lights, since their best-known appearance was in Lubbock, Texas. They have, however, appeared elsewhere. Next, we have the mysterious balls of green fire. Are they or are they not related to the luminous “Foo Fighters” that occasionally seem to accompany a plane or even engage it in a mysterious sort of shadowboxing? Finally, there are the “ghost” saucers that seem to hover suspiciously around a freshly launched balloon, and rush off at some unprecedented speed — presumably to report their findings. At least four such ghosts have been reliably reported.

Many of the records refer to some tremendous distance or speed. And here I ask this question: How can an observer on the ground, from a single station and with his eyes alone, give a reliable estimate of all three figures: distance, size and speed? If you think that this is easy, try it sometime — on the moon, for example.

The reported saucers move at varied angular speeds, either sideways or vertical. Their unknown actual speed depends on how far away they actually are. They may “veer” sharply at any given moment. At times, the images are extremely brilliant. Sometimes, they show a trace of structure, which some observers have associated with “windows” or “portholes” of a space craft.

They move without sound and hence seem to be controlled without any normal forces of power that we would ascribe to a craft on earth. The objects are generally round or oval and bear no resemblance to any known aircraft already built or being built on earth.

But are we justified in reversing these arguments and saying that, since no terrestrial craft could have such properties and since no human beings could withstand the tremendous buffeting that the flying saucers seem to get, the objects must perforce be space ships manned by beings of decidedly nonhuman characteristics? I ask again: Is this sweeping conclusion justified? Or shall we accept temporarily what seems to be a much more reasonable alternative: that the flying saucers are not material objects at all?

The one thing that can respond instantaneously to force is a light beam. You can stand at the foot of a high mountain and with a hand mirror flash a signal from base to peak and back again, a distance of more than 10 miles, in a tenth of a second or less. But, if we see something flashing over cliff and forest with a speed of 100 miles a second or accelerating with a force 1000 times greater than that of gravity, must we conclude that it is a manned craft?

Let us, then, accept as a working hypothesis the idea that saucers may be an optical phenomenon — though nonetheless real.

To me as a scientist, this was the only course along which to proceed. And the hypothesis that these were optical phenomena, taking place primarily in desert regions, inevitably brought the next logical consideration to my mind.

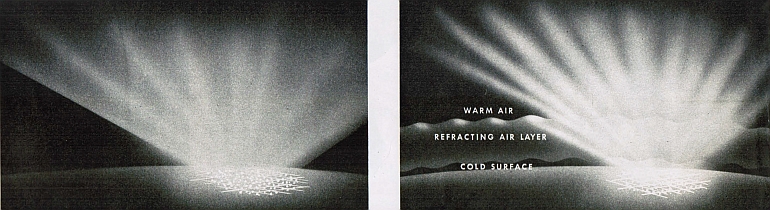

In the science of atmospherics, there is a well-known condition known as “temperature inversion.” It is simple enough. Normally, the air grows colder as one goes farther up from the surface of the earth. But sometimes the reverse is true, and a layer of warm air overlies layers of colder air.

During the war, I was a member and later chairman of the Wave Propagation Committee of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, which conducted a series of tests on the desert. We were studying radar images; but light behaves, in many ways, like radar. What we learned about the desert applies as much to light as to radar.

We learned that temperature inversions were, as we had expected, extremely common on the desert. During the day, the desert is extremely hot. At night (or even during the day under certain cloud conditions), the ground rapidly cools off. But the air cools more slowly. Thus, the air cools more quickly where it actually is in contact with the ground, but for some distance continues to get warmer with height. Then, well away from the ground, it begins to become cooler again.

Scientists have long known that regions of the atmosphere wherein the temperature changes rapidly with height can cause a mirage.

Mirage. That is the key to the whole problem of saucers. And, working on that assumption, I have been able to reproduce in the laboratory most of the essential features of the saucers. Much more study, both theoretical and experimental, is necessary before we shall understand this complicated problem in all its details. I am confident, however, that we can eventually produce and observe the phenomenon at about any time we wish to.

Mirage. A mirage is fundamentally an image caused by a lens of air. Since air lenses are almost never perfect, the world we see through them is distorted and unreal. Like seeing through spectacles that do not fit your eyes. Or looking in one of those highly curved mirrors in an amusement park.

And yet you see mirages every day, without really knowing it. As you drive along a highway on a hot day, the dark asphalt in the distance seems to be covered with water — a film that evaporates as the car advances. This is the ordinary mirage we familiarly associate with the desert: the thirsty traveler, the vision of a receding lake, and only sand. The water, of course, is an image of the sky, projected against the distant landscape. The light rays that produce the illusion traverse a path that is concave upward.

But give us a cool layer of air at the ground, as in the desert at night, and light rays will curve in the reverse direction, following along the surface of the earth.

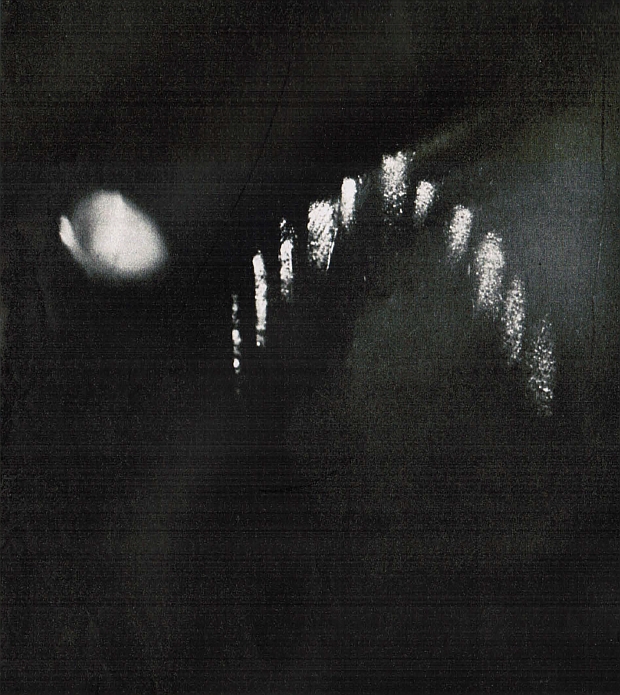

Where the daytime mirage projects the image of the sky against the earth, the nighttime desert variety projects the image of the earth against the sky. And hence, if we have distant lights — such as those of a city — these lights will appear to float in the sky. Moreover, if the intervening air contains waves or is turbulent to any degree, the lights will appear to move, riding in on the crest of a wave, like ripples of moonlight on the ocean. If the source is a line of distant street lamps, the images appear to fly in formation - the Lubbock Light phenomenon.

One further property of these temperature inversions serves to emphasize the effect and undoubtedly contributes to the daytime saucers. Daytime inversions are fairly common, but they usually lie higher than the ones that occur at night on the desert. You can often see them — or at least recognize their existence.

A column of smoke from a distant chimney will sometimes rise smoothly upward and then spread out horizontally to form a thin layer of smoke and haze. This ceiling occurs at the point of highest temperature. Smoke, dust and all kinds of general haze tend to collect in this layer. From below or above, you may not be aware of its existence. But as you pass through it, you see a fine black line extending from horizon to horizon.

On that famous day in June, 1947, when Kenneth Arnold of Boise, Idaho, spotted from his private plane nine distant saucers moving at “fantastic speeds” along the slopes of Mt. Rainier, he may well have been flying not too far from one of these layers of inversion haze. His was the observation that touched off the saucer scare.

Let us turn to the official Air Force release and quote Arnold himself: “I could see their outline quite plainly against the snow as they approached the mountain. They flew very close to the mountain tops, directly south to southeast down the hog’s back of the range, flying like geese. I watched for about three minutes — a chain of saucerlike things at least five miles long, swerving in and out of the high mountain peaks. They were flat like a pie pan and so shiny they reflected the sun like a mirror.”

In Arnold’s own story, there are several clues that should have pointed out the answer long ago. Anyone familiar with mountains knows that the ridges, where ascending currents of air from opposite sides meet and mix, are subject to the most violent drafts. From the Harvard and University of Colorado observatory at Climax, Colo., I have observed with a telescope the blowing snow on the ridges of 14,000-foot peaks, and have noted the billowing gusts rage along the “hog’s back.” It is indeed highly probable that the slopes of Mt. Rainier are equally turbulent. And, if their turbulence reaches upward into the haze, the warped layers would reflect sunlight and a progression of moves would make the crests seem to move with phenomenal speed.

And if you doubt whether mere bending or crinkling of a hazy layer could cause the bright reflection, note how a fold of a lace curtain — or piece of cheesecloth — similarly reflects the light. The reflection is brightest when the curvature is sharpest. Most daytime saucers are a variant of this phenomenon. The mirage effect is here of secondary importance.

The “ghost” balloons are perhaps the simplest of all mirage phenomena. The balloon itself is responsible. As it “punctures” some fairly high inversion, a large bubble of colder air settles down from above, forming in effect a sort of supermagnifying lens or telescope. This imperfect lens of air forms an image of the balloon. And, as the lens changes its size and shape, the distorted image darts wildly around, with phenomenal speed - like a reflection of the sun from a hand mirror.

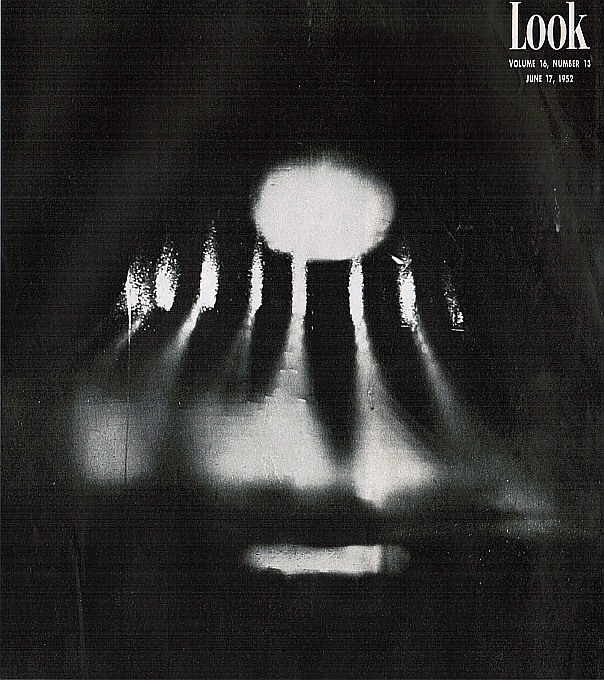

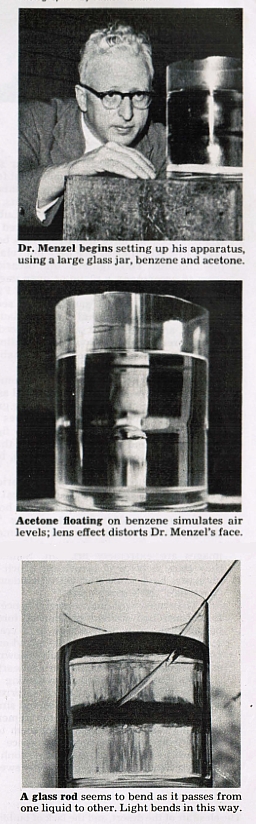

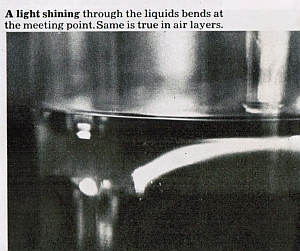

To demonstrate some of these effects — chiefly those associated with the luminous night saucers — I prepared a simple laboratory experiment, as follows: I filled a cylindrical jar half full of benzene and carefully floated a layer of acetone on top. Gentle stirring produced a narrow region where the chemical composition changed slowly upward. Benzene has optical qualities analogous to those of cold air and acetone to those of warm air. I thus reproduced in a small space what would ordinarily require miles of terrestrial atmosphere. The liquids produce remarkable effects.

A beam of light, focused diagonally upward from a small slide projector, would ordinarily strike the ceiling. But caught in the “inversion layer,” the beam obediently curved downward. Tiny globules of glycerine emulsified in the benzene scattered the light and made the beam visible. The original circular pinhole used in the projector was distorted into an oval shape and clearly marked with some pattern suggesting a surface structure.

Any motion of the liquid — produced as the result of a rocking - made the saucer slip about. Turbulence, caused by a delicate stirring of the medium near the light beam, gave dozens of flying disks. The color effects, resulting in part from the glycerine globules, were startling and beautiful. Finally, when I replaced the single pinhole with a row that simulated distant street lights, the resulting images behaved and looked like the Lubbock Lights.

These considerations do not explain everything. The green fire balls are still something of a mystery, though many will prove to be meteors. Prof. Fred L. Whipple of Harvard has called my attention to the fact that the color probably arises from the presence of magnesium in the meteor itself. This metal, well known to be an abundant constituent of the rock meteors, emits green light when incandescent. The reported slowness of motion may be due to great distance, associated with the clarity of the desert skies.

This mirage-phenomena theory includes the flying saucers seen on radarscopes. The same sort of conditions which cause optical mirages cause radar mirages as well, as any radar expert will hasten to tell you. They cause television mirages too. Everyone knows cases where a television station, normally miles out of range, suddenly comes in powerful and steady.

Also, the stress laid on the optical peculiarities of air over deserts should not be misleading. The temperature inversions of which I speak are common over the desert (and over coastal waters) but they are not limited to such areas. They can appear anywhere, and do. A bad smog, for example, is usually a sign of a temperature inversion. But they are more frequent over deserts, which explains in part the fact that saucer reports are more frequent over deserts.

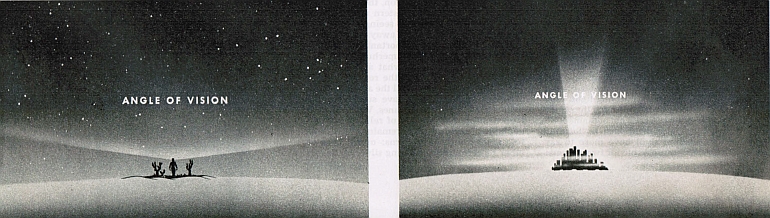

|

The clear air of the desert and the lack of buildings or of hills,

make it possible to see long distances, increase the number of

observed events. | In the city, the angle of vision is small and the sky is full of smoke and dust. Thus, even if the conditions were perfect for "saucers," fewer would be observed over cities. |

You, too, can have flying saucers in your home. Perhaps not as elaborate as the ones I have just described, but nevertheless adequate to demonstrate some of the effects. You may simulate the gradual bending that causes a mirage by using a sharp reflection at a water surface.

| In normal air, light from the ground simply spreads out into space. Outside its range, where the earth curves away, there is darkness and no strange phenomena. | With a temperature inversion, light bends in refracting layer of air. A ray of light will thus be seen in areas far distant from its source. |

Fill the kitchen sink to the brim and set up a candle or row of candles close to the edge along one side. A box with a series of pinholes illuminated by a light or candle is even better. Now face the lights from the opposite side of the sink, keeping your eye close to the water surface and see the bright reflections. Now have someone gently stir the water and produce waves. The lights will float and travel — and even show the disk-like form characteristic of a reflection from the trough of a wave. One can even reproduce the saucers with light reflected from the surface of coffee in a cup.

As I have said earlier, these experiments are suggestive rather than definitive. More work is necessary to prove the phenomenon. The analysis indicates, however, a clear plan for future study and research. I believe that these experiments will eventually cause the saucer scare to vanish — most appropriately, into thin air, the region that gave birth to it.

END