|

Science growls "Bunk!" But in

nervous times like these the

air-borne disk scare can — and

probably will — flare up again.

If you see a “saucer,” just do

what Air Chief Vandenberg did.

|

THE men who constitute the high command of the United States Air Force do not believe in flying saucers, disks, space ships from Mars — or Russia — which citizens of the United States have been reporting with increasing frequency since the atomic age burst upon the world. But they are not surprised that people are seeing them. The Air Force generals have seen saucers themselves — or, rather, what would have passed for saucers with less knowledgeable observers. No one knows better than an experienced airman what strange tricks the sun, stars and senses can play upon you in the wild blue.

Less than a year ago, Gen. Hoyt S. Vandenberg, the Air Chief of Staff, who was responsible for the decision to set up an Air Force project to sift the saucer reports, was piloting a B-17 bomber on a night flight when a strange, disk-shaped, lighted object streaked by somewhere over to his right. If the general had rushed into print with his experience, it would have been another incident in the Great Flying Saucer Scare. Instead of getting rattled, he just experimented a bit by moving his head at different angles, and, sure enough, he could reproduce the saucer at will. It was merely a reflection of a ground light on his window.

Lt. Gen. Lauris Norstad, who has served both the Air Force and Army as director of Plans and Operations, was flying back from Maxwell Field one night when both he and his copilot noticed a strange large object pacing them above. It failed to answer their identification signals. A little calm reconnaissance, however, established that the aircraft was nothing but the reflection of a star on a cloud.

Other generals have been bewildered - but not for long - by highly realistic illusions from ground air beacons and searchlights. Even Col. H. M. McCoy, who heads up the intelligence division at Air Materiel Command headquarters at Wright-Patterson Field, Dayton, Ohio, where saucer reports are screened, once thought he saw a disk while flying a P-51 fighter in broad daylight. It turned out to be a glint of sunlight from the canopy of another distant P-51.

Lt. Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, now the tough-minded Strategic Air Command boss, was particularly rough on saucer reports when he headed up the Air Force's research-and-development program at the height of the scare. He put his weather expert on the trail, and substantial proof was uncovered that one out of six of the then current crop of reports could be traced to a certain type of aluminum-covered radar-target balloon then in wide use. LeMay said nothing for publication, but soon thereafter, when a certain lieutenant colonel gave out a lulu of a story on how he, too, had seen flying saucers, the general rebuked him blisteringly by telegram ... and sent, it collect.

Gen. Carl Spaatz, the retired Air Chief, is another who gets indignant when he thinks of saucer hysteria, "If the American people are capable of getting so excited over something which doesn't exist," Spaatz told me, "God help us if anyone ever plasters us with a real atomic bomb." He added, "I can tell you unequivocally that the reported sightings of so-called saucers were completely unconnected with any form of secret research that the Air Force was conducting during my term as Chief of Staff."

It is no secret, of course, that the Russians are experimenting with supersonic aircraft and guided missiles just as we are. But if any of the things which have popped up over America for a few seconds or minutes are Soviet gadgets, the cold brain of Air Intelligence - which painstakingly sifts reports - would like to know how they do it and then return to home base without being seen by more people. It also is reasonable to wonder why, out of more than 250 reported saucers, not one has crashed so we could lay hands on a tangible bit of evidence; so far, Air Intelligence does not have so much as one loose nut off any unexplained object to examine.

The officers and technical experts assigned to Project Saucer — a nickname for the top-secret Air Force investigative effort — sometimes get to feeling they're living in a dream world, so utterly unfettered and mysterious are some of the reports they are assigned to evaluate. One of the most fanciful came from a Montana man who wrote in to tell of sighting a large, blue-white ball that had beamed a bright light at him. "I am perfectly sincere and do not drink," the Montanan said, "so the foregoing is absolutely the truth."

An Army pilot at Dayton, Ohio, had three or four teardrop-shaped objects come so close to his plane that he had to duck to avoid collision. Asked to describe them, he replied, "Take about one half gallon of water and dump it two hundred yards in front of an approaching aircraft about two hundred feet above it, with the water taking the shape of a teardrop -" In San Francisco, an aviation student strolling in Golden Gate Park said he was attacked by a mysterious light "like an electric arc," which seemed to have the power to "lower my hand like a sack of shot"; he said he had delicate skin and that it even left a bruise on him.

One of the main solutions to the reported phenomena lies in the aero-medical field. Both Air Force and Navy aero-medical experts have prepared volumes of research findings, spelling out in detail how vertigo, hypnosis and other sensory illusions affect pilots traveling at high altitudes and extreme speeds.

Vertigo is a loose term used to describe a condition of dizziness and stupor which pilots themselves call "the leans." Case histories set down by the Navy's School of Aviation Medicine at Pensacola have established that vertigo and self-hypnosis brought on by staring too long at a fixed light have caused pilots to dogfight with stars, to mistake round lights for other aircraft, flying saucers or what not, and to have outright hallucinations about things which weren't even there.

Wright Field aero-medical experts confirm these findings. In general, they feel that when a flier starts chasing an illuminated weather balloon or a star, and vertigo or hypnosis sets in, the pilot can come down and practically tell you how many rivets were on the nose of that Martian space ship.

The trouble with all the logical explanations, however, is that the person who has had, or thinks he has had, a sufficiently vivid encounter with a saucer is absolutely certain none of those explanations can apply to him. And in a number of the cases it is pretty hard to apply any of the logical explanations to the reported facts. You have to keep reminding yourself that even an experienced pilot laboring under strain and excitement finds it difficult to judge distances, altitudes and speeds accurately.

One particularly baffling case was the encounter of twenty-five-year-old George F. Gorman, of Fargo, North Dakota, a second lieutenant in the North Dakota Air National Guard, with an apparently disembodied and soundless white light that could climb, swoop and outmaneuver any jet plane now operating. I flew to Fargo to interview Gorman.

Gorman, a native of Fargo, is an employee of a farm-machinery company. He bears a good reputation for veracity and personal habits. During the war be instructed French flying cadets. He is articulate and above average intelligence. He has had several years of college education, and describes himself as an amateur student of Freud, physics and other subjects. Gorman insists be was not particularly conscious of the flying-saucer craze at the time of his reported experience, October 1, 1948, though the saucer excitement had been bubbling since June of the previous year.

At nine o'clock that evening, Gorman, who had been flying with his outfit, the 178th Fighter Squadron, decided to take a turn over the local stadium and watch a night football game which was in progress. The other planes landed, leaving him alone in the air in a fast P-51 fighter. He had been watching the game for about five minutes, which perhaps is significant. The aero-medical people would hold that concentration on the floodlights for that period might bring on vertigo or autohypnosis, but Gorman told me emphatically he was certain the lights had not disturbed his vision.

He first saw the light pass over the football field. He was at 4500-feet altitude and the object, he said, was “a littlie below.” It was "a small ball of clear white light, with no physical form or shape attached." It was perhaps six to eight inches in diameter, Gorman figured. It seemed to be making about 250 MPH at an altitude of 1000 feet. The light varied in intensity; it never was extremely bright and it blinked on and off.

To his surprise, he couldn't overtake it. He pushed his speed up to the limit, but the thing, which be thought had been traveling relatively slowly, exceeded him by at least 160 MPH. It seemed to Gorman, he said, that the light could outmaneuver and outrace him, though several times during the twenty-seven minutes he “fought” with it, he thought he came fairly close to the object. At one point be determined to ram it. He made a head-on pass, but lost his nerve and dived under it. During this pass, the object passed not more than 500 feet over his canopy, he estimated.

Later, the object initiated a pass at Gorman — “I had the distinct impression that its maneuvers were controlled by thought or reason,” he said — and he tried to ram it again. This time it pulled up and streaked to 14,000 feet, with Gorman following. He said that he blacked out several times during the violent maneuvers, but not for long. He also said be eventually climbed to 17,000 feet without oxygen, but is certain it did not make him groggy. Vertigo, he stated, was “absolutely out of the question.”

The object finally pulled away from him, climbing straight up until it was out of sight, Gorman said. Gorman was in touch with the Fargo airport tower during the encounter, broadcasting an account of his dogfight with the light. His story has partial corroboration. A sixty-seven-year-old flying grandfather, Dr. A. D. Cannon, an oculist, was in the air at the time in his plane. Cannon and a passenger, Einar Neilson, also had flown over the floodlighted football field. They saw a light in the air. It was “moving fast,” Doctor Cannon said, and he thought it might be a Canadian Vampire jet plane from Stevenson field near Winnipeg, some 200 miles from Fargo. After landing, Cannon saw a light twice from the ground; it seemed to him to keep a constant altitude, and definitely changed its direction from east-west to north-south.

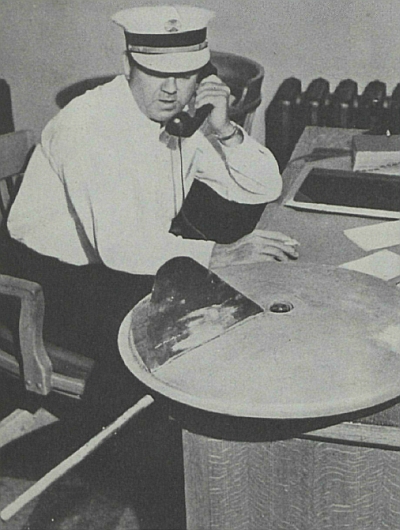

Also, Lloyd D. Jensen, the airport traffic controller, and Manuel E. Johnson, his assistant, Civil Aeronautics Administration employees and both extremely nonflighty citizens, each saw a strange light once, moving over the airfield.

I learned from the weather observer at the Fargo airport, George Sanderson, who is a member of Gorman's National Guard squadron, that a black weather balloon carrying a lighted candle had been released shortly before Gorman's strange encounter. But Sanderson, Jensen and Johnson, all experienced hands, insisted it couldn't have been the balloon-borne candle that perturbed the pilot. Sanderson said the balloon was being tracked by a theodolite, an observer's instrument, and that the wind direction and velocity were all wrong in relation to the course of the object Gorman said he was chasing. Sanderson said his assistant tracked balloon until it disappeared, just before Gorman landed, at 12,000 feet.

Another solution suggests itself: Fargo is only about 200 miles away from the Operation Skyhook base near Minneapolis, where the Navy is releasing giant, light-bearing plastic balloons as part of a project to study cosmic rays. These balloons travel high and fast, and have frightened the wits out of observers wherever they have drifted. Navy scientists in Washington said it is entirely possible one of their balloons drifted over Fargo that night.

The Air Force checked across the border to determine if any Canadian jets had been skylarking over North Dakota that evening, and were assured that such was not the case. None of the ground witnesses heard the banshee whine typical of Canadian jets, anyway. Investigators even tested Gorman's fighter with a Geiger counter, but got a negative reaction for atomic radiation.

So it adds up to a sweet mystery. Was Gorman suffering from a combination of vertigo and confusion with a balloon or ground light? If so, how is the testimony of the ground witnesses, who certainly didn't have vertigo, to be explained rationally? Or did Gorman stumble onto something that has been kept secret successfully by the Air Force, or some other nation, or our friends up on Mars? Personally, after my investigation, I'll vote for the balloon and vertigo.

An encounter similar to Gorman's as recently as last November eighteenth at the Air Force's great Andrews Field base on the outskirts of Washington, D. C. At 9:45 P.M., Henry G. Combs, a twenty-five-year-old second lieutenant in the Air Force reserve, was returning from a night mission with his squadron. Combs, a quiet, serious physical-culture enthusiast, is a young man who trained with the Air Force during the war, but never got overseas; he is so anxious to get back on active duty that he even has written President Truman asking if anything can be done.

As he was preparing to land, Combs spotted something. It was a “dull gray globe” six feet thick and twelve to fifteen feet across. It gave off a sort of frosty light and had rough edges; no blinking, no exhaust flames.

Just as Gorman did, Combs gave chase. For the next ten minutes the thing led him through astounding maneuvers changing its airspeed, Combs related, from seventy-five to 600 MPH and varying its altitude from 2000 to 7500 feet. In the back seat of his T-6 trainer was 2nd Lt. Kenwood W. Jackson, who was unhappy about the whole business. Jackson confirmed that a light was seen and chased, though his description of what happened differs somewhat from Combs'. He wanted to radio the control tower, but Combs wouldn't let him.

Combs' encounter ended, he said, when he stood his T-6 practically on its tail and flashed his landing lights squarely on the thing. At this point, Combs said, the thing streaked away toward the East Coast at 600 MPH and disappeared.

Here again it is a distinct possibility that a pilot was mixed up by a combination of vertigo and a balloon. However, the continued testimony of pilots that these “things” could outmaneuver them bothered me, as balloons are notoriously nonmaneuverable. So, while at Wright Field, I asked a pilot to go up and make a few passes at a weather balloon and see how it looked to him. He came down and told me, with some surprise, that, when he turned around the balloon, it definitely appeared to be turning at the same rate as his plane, and at times it even seemed to be turning faster than his aircraft.

Another wide area through which Project Saucer investigators have had to plow is the rich, intangible field of hallucinations, hoaxes and mass hysteria. For example, a man from Zelienople, Pennsylvania — who said he was “strictly scientific” in his thinking — wrote to the Air Force: “I am prepared to state that careful study and research has absolutely CONVINCED me that these 'Objects X' are creations of realms above or beyond our sphere; are, if you please, GHOST objects or craft, propelled by paranormal teleportion (the telekinesis of the poltergeist manifestation). . . . They are controlled by intelligent, ghostlike, invisible beings or animals bearing, I believe, very little likeness to human beings.”

As for hoaxes: Near Black River Falls, Wisconsin, at the height of the Great Flying Saucer Scare, a “flying disk” was found at the county fairgrounds. The finder obligingly placed it on exhibition at fifty cents a look until the local chief of police confiscated it. FBI agents flew all the way up from Milwaukee in a chartered plane to see it. It was found to be a crude concoction of plywood and cardboard, with pieces of propellers and radio cells mounted on it — strictly an opportunistic fake.

A “flying disk” fell in the street in a Southern city. It was composed of aluminum strips, fluorescent-lamp starters, condensers, rivets, screws and copper wire. A little investigation resulted in a confession from the culprit, the superintendent of an electric-fan factory, who said he concocted the device and threw it from the roof of the factory, hoping to scare his boss, who was getting into his car.

Mass hysteria is a phenomenon that has fascinated philosophers and psychologists for ages; there is no limitation on what impressionable people will think they've seen if someone starts a sufficiently convincing rumor. Even an honest rumor will do the trick.

It is a jittery age we live in, particularly since our scientists and military spokesmen have started talking about sending rockets to the moon and about experiments to by-pass the law of gravitation by creating a man-made planet that will streak off the earth at 25,000 miles per hour or so and start circling in our orbit. Though we have not yet produced the rocket-to-the-moon and the homemade satellite, it is small wonder that harassed humans, already suffering from atomic psychosis, have started seeing saucers and Martians.

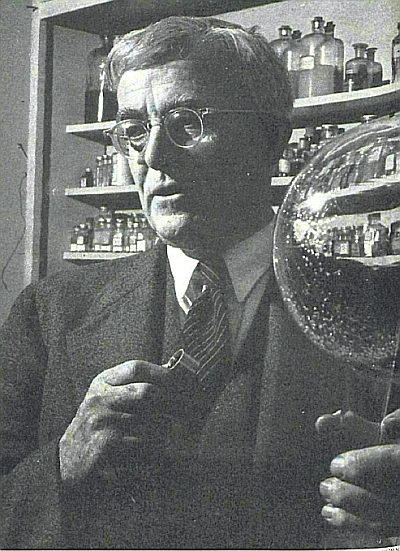

Perhaps the most outspoken foe of the flying saucer in the United States is Dr. Irving Langmuir, the distinguished scientist and Nobel Prize winner. Doctor Langmuir, associate director of General Electric's Research Laboratory at Schenectady, has spent a lifetime debunking what he calls “pathological science” — that is, untruthful scientific theories which were carelessly accepted as truthful until someone came along to prick a hole in them — and he lumps saucers in this category. He also happens to he a member of the Air Force's Scientific Advisory Board. Though Doctor Langmuir speaks on saucers in his nonofficial capacity as a scientist, he has given the Air Force an earful on the — as it appears to him — absurdity of it all.

Doctor Langmuir was one of the first to point out that Venus was close to its peak brilliance the day an unfortunate National Guard pilot killed himself chasing a saucer in Kentucky. When shown a picture that someone took of a heel-shaped “saucer” flying over Phoenix, Arizona, he acidly inquired if anyone had taken the trouble to determine whether there was a violent squall over Phoenix that day. “To me,” he said, “the picture has all the scientific aspects o£ a piece of tar paper, or a torn blanket, or a collapsed balloon, tossing in a high wind.

“One of the characteristics of a thing that isn't so,” Doctor Langmuir continued, “is the impossibility of bringing it out into the open. If a man tells me that two and two equal five or that he has seen a flying saucer — I don't feel I have to prove he is wrong. I feel the burden is on him to prove that he is right.”

I asked Doctor Langmuir what he would advise the Air Force to do about flying saucers. He snapped his answer, “Forget it!” The Air Force, I suspect, would like to forget it. But then something new comes along like the strange adventure of two Eastern Air Lines pilots with what seemed to be a flameshooting, double-decker space ship, and Wright Field has to send out another team of investigators.

Of all the so-called saucer stories, the most difficult to rationalize is the account of what Eastern Air Lines pilots Clarence Shipe Chiles and John B. Whitted said they saw twenty miles west of Montgomery, Alabama, on the morning of July 24, 1948. At 2:45 A.M., the two men were flying a DC-3 airliner into Atlanta, Georgia. Chiles, a thirty-one-year-old Tennessean, wartime lieutenant colonel and former commanding officer of the Air Transport Command's Ascension Island base, was captain of the ship. He has had 8500 hours in the air and has flown more than 1,000,000 miles. Whitted, a thirty-year-old North Carolinian, a wartime pilot of B-29 Superfortresses, was his copilot.

Chiles and Whitted told me their story during an interview I had with them in Atlanta. “We were flying at five thousand feet on VFR - visual flight rules,” said Chiles. “That meant we were even more alert than normally for stray aircraft, for we were on our own rather than at a specified altitude assigned by the CAA.

“I saw the thing first. 'Here comes a new jet job!' I yelled to John. He saw it too. Then we knew it was like no jet job we'd ever heard about. We had five to ten seconds to look at it. The moon was full and the object came quite close — not more than a mile away, I thought, and John here thought it was even closer. It was traveling on a southwesterly course — exactly opposite to our direction. Its velocity, allowing for our own air speed, could have been anywhere from five hundred to seven hundred miles per hour — I'm sure it was faster than any jet I've ever seen flown.”

Despite the flashing speed with which the airliner and the reported object would have passed each other, both pilots noted a wealth of details. They agreed the object was at least 100 feet long. Chiles thought the fuselage was somewhat more streamlined than that of a B-29. Whitted, on whose side of the cockpit the object passed, thought it was nearly twice the diameter of a Superfortress. But the hair-raising thing to them, they said, was that the thing looked like a plane, flew like a plane, but had no wings.

“We couldn't have been mistaken about it — the illumination from both the moon and the thing itself were too good for that,” Chiles continued earnestly. “There were two rows of windows, or 'breathers,' along the fuselage. A highly intense white light — it was much too bright to be used for interior illumination, so it may have been from a power plant — came through these windows. And a fluctuating blue flame danced along the belly of the thing. From an exhaust in the tail of the object came a trail of red-orange flames that shot out for some fifty feet.”

Chiles and Whitted agree on the above details. Chiles also paid particular attention to the nose of the thing, and observed that it had a radarlike protrusion from its snout that “looked like a swordfish,” and that there were four to six metallic-looking objects in front that resembled streamlined windshields, or louvers.

As soon as the thing had disappeared, by pulling up sharply and climbing. Chiles and Whitted said, they started gaping at each other. They said they couldn't believe it. Chiles went back in the darkened interior of the plane and started asking the passengers if they'd seen anything. Apparently, the only one who had been looking out of the window at that hour was Clarence L. McKelvie, of Columbus, Ohio. He had seen a bright streak of light whiz by the window, but had observed no form or details. He told Air Force investigators that Chiles seemed genuinely excited when he came back into the cabin.

Chiles and Whitted still say they do not know what to think; they say they are certain that they were not suffering from hallucinations and that what they saw was a manufactured object — not a meteor — and unlike any aircraft or missile known to them. They immediately checked with the nearest control tower to ascertain if there were any commercial or Army aircraft in their vicinity, and were told there were not. The Air Force has confirmed it had nothing flying in the area at the time.

Both men are married and fathers. They had nothing to gain by their story, for it was bad publicity. Neither has tried to profit by the incident, nor were they responsible, so far as I could learn, for the story being given out to the newspapers. Chiles told me he didn't even report the incident to his superiors until the middle of the next day, and that he did so then only because he was worried that if the Army had any experimental craft flying in those lanes it might collide with some airliner.

The high command and the research-and-development chiefs of the Air Force gave me unequivocal assurance that nothing tested at Eglin Field, which is 130 miles to the south, possibly could answer the description of the Chiles-Whitted object. Not even the slow V-1 buzz bomb has been launched from there within the past two years, they said. They also pointed out that a guided missile does not perform in the manner described by the two pilots, and that a V-2 rocket would travel so fast they couldn't have seen it from their cockpit. As for aircraft, they said, maybe a wingless fuselage could fly, but it would have to have nothing short of atomic power to lift it from the ground.

While the Air Force finds it difficult to believe that the heavens are populated with inexplicable skimming saucers, diving disks, bounding balls or spooky space ships, even when the testimony comes from such excellent witnesses as pilots Chiles and Whitted, it does want to know about such things.

So, if you're standing out in your back yard or flying your plane some afternoon or evening, and see one of these things in the sky, here is what the Air Force would like to have you do: Before running for the telephone to call your favorite newspaper, take some mental notes on what and where the object is, and what it is doing. If possible, try to estimate how far it is from you by making comparisons with some fixed object, such as a town or mountain. If there is a mountain handy, you may be able to make some guess as to the object's altitude. Try to estimate its apparent angle above the horizon; if you're viewing it from the ground, hold your arm straight up — that's ninety degrees — and guess the angle of the object in relation to the ninety-degree mark. Try to estimate its size; if you have a rough idea how far you are from it, you can get a “fix” on its size by holding up a dime — or any small object, such as the blunt end of a pencil or the tip of your thumb — and seeing how much of the object is obliterated by the dime.

Take a photograph or make a sketch if you can; if not, remember all you can about its appearance and whether it has any protuberances. Carefully note its color and whether or not it reflects or projects any lights. Note what maneuvers it engages in and what it appears to be made of; whether it makes any sound, spurts flames, sparks or smoke or gives out an odor. If it is in horizontal flight, try to estimate its speed by timing how long it takes to travel between two points. Note weather and cloud conditions, and observe how it disappears — whether it explodes, fades or vanishes behind clouds. And, of course, if it is obliging enough to crash or shower down any fragments in front of you, by all means secure the pieces — if they seem harmless.

Then sit down and write a letter containing all this information to Technical Intelligence Division, Air Materiel Command Headquarters, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio. At the same time, maybe you'd better buttress yourself with an affidavit from your clergyman, doctor or banker.

If you've really seen something and can prove it, you may scare the wits out of the United States Air Force, but it will be grateful to you.