The 1948 Berlin Crisis: Talk of War

Three years

after the Nazi surrender, divided Germany continued to be a major trouble

spot. Friction between Stalin and the three Western Allies over the

governance of the defeated nation grew more intense as 1948 progressed,

and secret military intelligence estimates exacerbated war worries in

the Pentagon. In early March, General Lucius Clay notified Army Intelligence

that he had received indications that the Soviets were preparing for

armed conflict, sending the Washington military establishment into an

alert posture.

The Soviets

reacted with anger to signs that the western Allies were planning to establish

an independent government in the Western Zone of Germany. At the end of

March, the Soviet representative walked out of a meeting of the Allied

Control Council. A few days later, the Soviets notified the other powers

that Westerners attempting to travel to Berlin, deep inside the Soviet

Zone, would be required to pass through Soviet inspections. The next day,

some rail lines into Berlin were shut down as a token of Soviet resolve.

Air Force Chief of Staff Spaatz notified the Air Staff that he wanted

Alaskan air defenses augmented immediately, and issued a top secret order

that Alaskan radar stations were to go on 24-hour watch.

The US

Air Force stepped up supply deliveries to Berlin in the first few days

of April, and the Soviets countered this with intimidation tactics.

On April 5, a British airliner on a scheduled flight within one of the

defined air corridors to Berlin was suddenly buzzed head-on by a Soviet

Yak-3 fighter. The fighter streaked past the transport, turned, then

made another pass at the airliner's nose. The aerial game of chicken

ended in tragedy. The two planes collided and went down, killing ten

passengers and crew in addition to the Soviet pilot.

The US

detonated the sixth atomic bomb in a test called "Sandstone X-Ray"

on April 14 -- the first nuclear test in nearly two years.

When Navy

Secretary John Sullivan told a Senate hearing that unknown submarines

had been sighted in the Pacific, a Washington newspaper screamed that

"Russian Subs Prowl West Coast Waters."

On June 7, the Western Allies announced that a West German government would be set

up within a year. The Soviets reacted by pulling out of the four-power

administrative commission for Berlin.

The Western

Allies announced replacement of the German Reischsmark with a new currency,

the Deutschmark, on June 18th. The Soviets refused to recognize the new

money. It was a de facto admission that Germany would be economically

as well as politically sliced apart.

The post-war

Four Power government of Germany was dead. As of midnight on June 20,

all traffic into the Soviet Zone of Germany was halted by hostile Russian

border guards. Three days later, the Soviets began a blockade of the

isolated city of Berlin.

On June 28,

representatives of the US State and Defense Departments met with the Joint

Chiefs of Staff to discuss the possibility of war. President Harry Truman

and the National Security Council believed that Stalin and the Politbureau

did not want war, but mulled over a proposal by General Clay to send armed

convoys through the blockade as a test of Soviet will. Would the Russians

allow them to pass? Truman was in the middle of a tough reelection fight

against Republican Thomas Dewey, and decided that air power, and aerial

supply of Berlin, were less risky alternatives. He also resisted pressure

from Defense Secretary Forrestal to transfer custody of nuclear weapons

from the Atomic Energy Commission to the Pentagon.

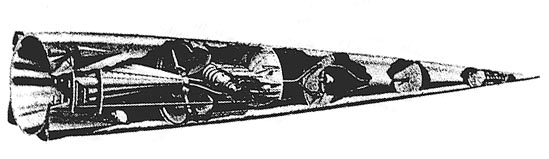

On July 16,

the US Air Force and the British Air Ministry announced the deployment

of two US B-29 medium bomber groups to England. The next day,

thirty B-29s of the 28th Bomb Group flew to RAF Scampton, and on the 18th,

thirty more B-29s deployed to RAF Lakenheath. On the 20th, 16 F-80 Shooting

Star jet fighters from Selfridge AFB in Michigan flew to Germany by way

of Iceland and the UK.

The same

day, a strange, Zeppelin-like thing was seen in the sky over Arnhem, in

the Netherlands.