|

Most human affairs happen without leaving vestiges or records of any kind behind them. The past, having happened, has perished with only occasional traces. To begin with, although the absolute number of historical writings is staggering, only a small part of what happened in the past was ever observed…And only a part of what was observed in the past was remembered by those who observed it; only a part of what was remembered was recorded; only a part of what was recorded has survived; only a part of what survived has come to the historians’ attention; only a part of what has come to their attention is credible; only a part of what is credible has been grasped; and only a part of what has been grasped can be expounded or narrated by the historian. |

Following the UFO History Workshop and the subsequent formation of the Sign Historical Group in 1999, it was evident that one area lacking in the preservation of the history of the UFO phenomenon was the archiving of spoken memories and personal commentaries of historical significance through recorded interviews. Since I had some expertise conducting interviews and was versed in the technology, I was inspired to form the Sign Oral History Project in order to preserve important historical information that may otherwise be lost and ultimately make it available for scholarly study. Many individuals who have personal knowledge of some aspect of UFO history, whether witnesses; Air Force project officials and personnel; scientists involved in government-funded research; investigators and individuals involved in the social aspects of the phenomenon have never been interviewed about information and perspectives that only they can provide. Time is running out. The initial progress of the project has been excellent and we have managed to collect over 70-videotaped interviews with the help of many colleagues.

Any comprehensive discussion regarding the standards and practice of producing oral history is beyond the present scope, however, central to the issue is the maxim that oral history must be based firmly on research. This is a critical point and speaks directly to the evidentiary value of oral history. Many critical essays have been written addressing the fear that the ease of tape recording will mean, “a downgrading both of source material and what is made from it” for future scholars. The late Barbara Tuchman charges that oral history gathers trash and trivia with all the discrimination of a vacuum cleaner. Of course, one might well respond that one researchers trash is another’s gold. Nevertheless, the critique is not without substance since standards have been slow in developing. Oral history is in many ways similar to oral tradition (unwritten knowledge passed on through successive generations) since it can introduce error or falsification and requires comparative evaluation for veracity. If the human memory is a selective record, then recollections (not concurrent to the subject or event) are still further selective and the evidentiary value decreases towards abstraction. However, relevant to SOHP subject matter, some researchers (including myself) find oral evidence reliable for the unique event, which leaves a powerful and sometimes life-altering impression on the interviewee.

The memoir that emerges as a result of a mutually creative process is a new kind of historical document. The fact that the document is mutually created contributes to both the strength and weakness inherent in oral history memoirs. Nevertheless, with caveat emptor in mind, the problems of evaluating spoken testimony are not so different from those inherent in the use of other primary sources. To be most effective, oral history must be well grounded in sound analysis and in a thorough knowledge and understanding of all available and pertinent sources, if it is to produce the best and most reliable oral documentation.

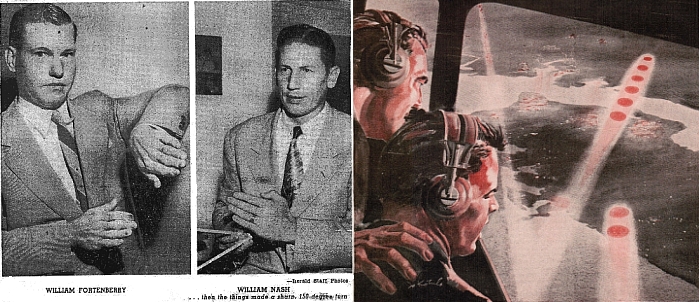

The following article was inspired by a recent SOHP interview with Bill Nash at his home in Florida on January 4, 2002. Many readers will be familiar with Captain Nash’s July 14, 1952 UFOs sighting, which remains one of the exceptional reports despite the fact that the total sighting lasted only twelve seconds. Still, it was a mere twelve seconds and the right-person at the right time, which left an indelible mark on the history of the phenomenon.

Meeting Bill Nash made me realize why this particular sighting is still regarded as one of the “classics.” Aside from the exceptional qualifications of both pilots, the genuine compassion and strength of character revealed by Bill Nash in the course of the interview became clearly evident. Documents seldom convey the way that people thought, but interviews provide a unique opportunity of assessing an interviewee’s character. I must admit that in this case I have been unashamedly seduced.

Thomas Tulien is a documentary filmmaker and co-chair of the Sign Historical Group

References:

Dunaway, David K. & Baum, Willa K., Oral History: An Interdisciplinary Anthology. 2d ed, AltaMira Press (Walnut Creek, CA 1996).

Tuchman, Barbara, “Research in Contemporary Events for the Writing of History,” in Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the National Institute of Arts and Letters, 2d ser., no. 22 (New York, 1972), p. 62.

On the evening of July 14, 1952, a Pan American World Airways DC-4 was on a routine flight, ferrying from New York to Miami with ten passengers and a crew of three, including, Captain F. V. Koepke, First Officer William B. Nash and Second Officer William H. Fortenberry.

The sun had set an hour before though the coastline was still visible, and the night was clear and almost entirely dark. With the aircraft set on automatic pilot, while cruising at 8000 feet over the Chesapeake Bay approaching Norfolk, Virginia, they were due to over fly the VRF radio range station in six minutes and make a position report. In the mean time, since this was Fortenberry’s first run on this course, Nash, in the left pilot’s seat, was orientating Fortenberry by pointing out landmarks and the distant lights of the cities along the route.

Nash had just pointed out the city of Newport News and Cumberland, ahead and to the right of the plane, when unexpectedly a red-orange brilliance appeared near the ground, beyond and slightly east of Newport News. The brilliance seemed to have appeared all of a sudden and both pilots witnessed the startling appearance at practically the same moment. In the excitement someone blurted out, “What the hell is that?”

Captain Nash later described their initial observations…

“Almost immediately we perceived that it consisted of six bright objects streaking toward us at tremendous speed, and obviously well below us. They had the fiery aspect of hot coals, but of much greater glow, perhaps twenty times more brilliant than any of the scattered ground lights over which they passed or the city lights to the right. Their shape was clearly outlined and evidently circular; the edges were well defined, not phosphorescent or fuzzy in the least and the red-orange color was uniform over the upper surface of each craft.”

“Within the few seconds that it took the six objects to come half the distance from where we had first seen them, we could observe that they were holding a narrow echelon formation, a stepped-up line tilted slightly to our right with the leader at the lowest point, and each following craft slightly higher. At about the halfway point, the leader appeared to attempt a sudden slowing. We received this impression because the second and third wavered slightly and seemed almost to overrun the leader, so that for a brief moment during the remainder of their approach the positions of these three varied. It looked very much as if an element of "human" or "intelligence" error had been introduced, in so far as the following two did not react soon enough when the leader began to slow down and so almost overran him.”

What occurred next utterly astonished the pilots. The procession shot forward like a stream of tracer bullets, out over the Chesapeake Bay to within a half-mile of the plane. Realizing that the line was going to pass under the nose of the plane and to the right of the copilot, Nash quickly unfastened his seat belt so that he could move to the window on that side. During this interval, Nash briefly lost sight of the objects, though Fortenberry kept them in view below the plane and both would later recollect…

“All together, they flipped on edge, the sides to the left going up and the glowing surface facing right. Though the bottom surfaces did not become clearly visible, we had the impression that they were unlighted. The exposed edges, also unlighted, appeared to be about 15 feet thick, and the top surface, at least, seemed flat. In shape and proportion, they were much like coins. While all were in the edgewise position, the last five slid over and past the leader so that the echelon was now tail-foremost, so to speak, the top or last craft now being nearest to our position.”

This shift had taken only a brief second and was completed by the time Nash reached the window. Both pilots then observed the discs flip back from on-edge to the flat position and the entire line dart off to the West in a direction that formed a sharp angle with their initial course, holding the new formation. The pilots had noticed that the objects seemed to dim slightly just prior to the abrupt angular turn and had brightened considerably after making it. Attempting to describe the objects extreme actions, Nash proposed, “The only descriptive comparison we can offer is a ball ricocheting off a wall.”

An instant later, two more identical objects darted out past the right wing, from behind and under the airplane at the same altitude as the others and quickly fell in behind the receding procession. They observed that these two seemed to glow considerably brighter than the others, as though applying power to catch up. As they stared after them dumbfounded, suddenly the lights of all of the objects blinked out, only to reappear a moment later, maintaining low altitude out across the blackness of the bay, until about 10 miles beyond Newport News when they began climbing in a graceful arc that carried them well above the plane’s altitude. Sweeping upward they randomly blinked out and finally vanished in the dark night sky. Describing the disappearance of the objects some years later, Nash wrote,

“As they climbed, they oscillated up and down behind one another in a irregular fashion, as though they were extremely sensitive to control. In doing this, they went vertically past one another, bobbing up and down, (just as the front three went horizontally past one another, as the initial six approached us. This appeared to be an intelligence error, ‘lousing up the formation’) — they disappeared by blinking out in a mixed-up fashion, in no particular order.”

Their bewildered initial reaction is best affirmed in the words of Nash…

“We stared after them, dumbfounded and probably open-mouthed. We looked around at the sky, half expecting something else to appear, though nothing did. There were flying saucers, and we had seen them. What we had witnessed was so stunning and incredible that we could readily believe that if either of us had seen it alone, he would have hesitated to report it. But here we were, face to face. We couldn't both be mistaken about such a striking spectacle.”

The time was 8:12 Eastern Standard Time. As the reality of their experience dawned on them the first question which came to mind was whether anybody else onboard had seen the spectacle. Fortenberry went through the small forward passenger compartment, where the captain was intent on paper work. In the main cabin a cautious inquiry whether anyone had seen anything unusual produced no results.

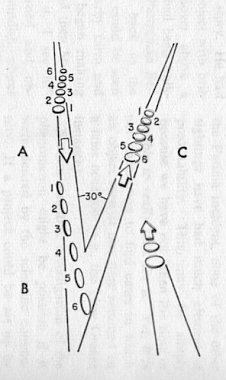

At "A", during approach, six UFOs held a stepped-up echelon formation. Flipping on edge at "B", followers overrode the leader until, in reverse order at the V-point, they flipped flat again and the echelon darted in a new direction, appearing aligned from the observers' point of view. At "C", after a brief blink-out, the six were joined by two from behind the airliner. |

Back in the cockpit, the pilots radioed Norfolk and gave their position according to schedule, and upon receiving confirmation added a second message to be forwarded to the military:

"Two pilots of this flight observed eight unidentified objects vicinity Langley Field; estimate speed in excess of 1,000 mph; altitude estimated 2,000 feet." At this point, Captain Koepke came forward and took over control of the DC-4 while Nash and Fortenberry went to work reconstructing the sighting.

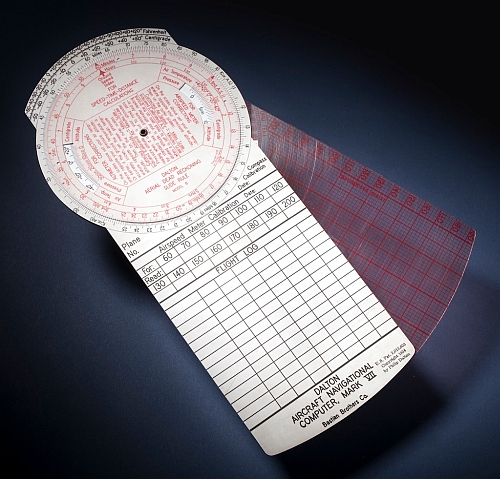

With a Dalton Mark 7 computer they determined the objects' angle of approach and the same for the angle of departure. The difference between the two was about 30 degrees; therefore, the objects had made a 150-degree change of course almost instantaneously.

They were able to accurately determine their position visually and by reference to their position to the VHF range at Norfolk. The objects first appeared beyond and to the east of Newport News and came toward the DC-4 in a straight line, changed direction beneath the plane and departed in a straight line to the West once again passing a suburban edge of Newport News and seemed to travel out over a dark area before they began to climb steeply into the night sky. They determined that Newport News was 25 miles away and added the additional 10 and 30 miles that they estimated the objects had traveled in each direction, arriving at a total distance of 90 miles. To be conservative they decided to use 50 miles, since they had seen them travel at least that distance. Determining the time duration of the sighting was not so straightforward. Wanting to be accurate, they reenacted the exact sequence of events seven times, and using the panel stopwatch clocks determined that the time period did not exceed 12 seconds each time. Again, to be conservative they adopted 15 seconds in the final computation, which meant that the objects were flying at the rate of 200 miles per minute, or 12,000 miles per hour!

They estimated that the objects were slightly more than a mile below the plane, or about 2000 feet above ground level, and by mentally comparing their appearance with the wingspread of a DC-3 at that distance, judged the size to be approximately 100 feet diameter and 15 feet thick. Determinations of distance, size and speed are always open to question by the fact that the objects observed were unidentified phenomena. However, this particular incident was especially unique in the sense that the pilots observed the objects between the ground and the plane. Most sightings occur against an empty sky without any standard of comparison to known objects or distance, but in this case the planes altitude of 8000 feet established a finite distance for reference. Nash later qualified his ability to estimate the altitude of the objects in a letter to astrophysicist, Dr. Donald H. Menzel.

“We both had flown many thousands of hours at either 7000 or 8000 feet, because these altitudes were high enough to avoid most turbulence but not so high as to starve us for oxygen. Hence, a sort-of “instinct-judgment” about the height of objects gradually developed. If after 10,000 hours of flying at the same altitude a pilot cannot judge if something (even an unfamiliar something) is halfway between his plane and the ground, and split that in half again, he best quit. Our judgment, after seeing these things travel nearly a hundred miles, and observing them both from a distance and almost directly beneath us, was that they were holding 2000 feet for most of the observed time.”

Further, both Nash and Fortenberry had served in the Navy during the war in which Nash flew patrol bombers for the Naval Air Transport Service patrolling between the African and South American coastlines in search of German submarines. Fortenberry served in the U.S. Navy Air experimental wing for two years and was well aware of aeronautical developments for the time. In naval training, both pilots had received intensive instruction in aircraft identification and had learned to identify every ship in the German Navy.

While Nash and Fortenberry were still discussing the matter, the lights of a northbound airliner came into view on a course about 1,000 feet above. Ordinarily the head-on approach of two airliners at 500 mph seems fairly rapid. But in this instance, compared to the streaking speed of the discs, the oncoming plane seemed to be standing still. If any normal happening could have increased the effect of the night's experience, it was just such a commonplace event.

They landed at Miami International Airport shortly after midnight. Upon entering the operations office, they found a copy of the message they had transmitted to the military through Norfolk, with an addition: "Advise crew five jets were in area at the time." This didn't exactly apply since the things they had seen were eight in number, and they were dead sure they were not jets.

At 7 A.M. Air Force investigators telephoned and an appointment was set for an interview later that morning. USAF Wing Intelligence officer Major John H. Sharpe and four officers from the 7th District Office of Special Investigations met Nash and Fortenberry at the airport. In separate rooms, the pilots were questioned for one hour and forty-five minutes and following that, for a half-hour together. The pilots were duly impressed by the skill and thoroughness of their interrogators. Questions had been prepared in advance and posed individually to the two pilots in order to evaluate their recall. Map overlays were compared and they had a complete weather report for the area, which coincided with the previous night’s flight plan. It stated; 3/8 Cirrus clouds about 20,000 feet. No inversion and a sharply clear night, probably unstable air. Visibility was unusually good. Following the interview, the investigators advised the pilots that they had already received seven additional reports from persons who had witnessed similar incidents within 30 minutes, in the same area. The best was from a Lt. Commander and his wife who described a formation of red discs traveling at high-speed and making immediate directional changes without a turning radius. Being told that their particular experience was by no means unique surprised the pilots.

None of these reports appear in the official Blue Book files, though three reports requested by ATIC in August describe multiple objects cavorting over Washington D.C. at 9:00 A.M., the morning of the sighting. Fortunately, NICAP retained copies of some of the confirmatory reports for the evening of July 14, which were published in the Norfolk newspapers. Although none of the reported sightings appear to describe the identical maneuvers that the pilots witnessed, a couple are sufficiently similar to be taken as reasonable substantiations. For example, one witness stated that,

“She and a friend were sitting on a bench in Stockley Gardens when they saw what appeared to be flying saucers ‘circling overhead and then going north.’ She said they saw seven or eight altogether ‘the first three white and the others were yellow and red.’”

In a letter to the editor of the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, the naval officer from the cruiser Roanoke, apparently mentioned to Nash and Fortenberry during the OSI investigation, reported that he had sighted eight red lights in the direction of Point Comfort that proceeded in a straight line and then disappeared. He saw the objects at about 8:55 P.M. Eastern Daylight-Saving Time, approximately 15 minutes before the pilot’s sighting, as he was driving towards the Naval base for a 9:00 P.M. appointment.

Especially interesting is that as a result of the press coverage of the Pan American pilots sighting the following day, Paul R. Hill, an aerodynamicist at the NASA-Langley facility, decided to watch the sky for UFOs on the evening of July 16. Expecting “conformance to pattern” he parked at the waterfront a little before 8:00 P.M. and soon observed two amber-colored objects approach from the South and turn West taking them directly overhead. At this point, the objects curiously appeared to be alternatively jumping forward of each other slightly. Then after passing zenith, they made an astounding maneuver. They began to revolve around a common center, and after a few revolutions, switched to the vertical plane! Within a few more seconds two more similar objects joined the first two before all four headed south. Hill later wrote,

“Up to that point I had been just a fascinated spectator. Now they had convinced me. At that moment, I realized that here were visitors from another world. There is a lot of truth in the old saying, ‘It’s different when it happens to you.’ It was within my line of business to know that no Earthcraft could remotely approach those maneuvers.”

This sighting prompted Paul Hill to a life-long study collecting and analyzing sightings’ reports for physical properties and propulsion possibilities in an attempt to make technological sense of the unconventional objects. The study was eventually published posthumously, under the title, Unconventional Flying Objects: A Scientific Analysis (Hampton Roads, 1995), in which Hill presents his thesis that UFOs “obey, not defy, the laws of physics.”

At the time of these sightings flying saucers had been big news for many weeks and the staff of nine at Project Blue Book were swamped with sighting reports, far more than they could properly deal with. By mid-July they were getting about twenty reports a day and frantic calls from intelligence officers at every Air Force base in the U.S. The reports they were getting were good ones and could not be easily explained. In fact, the unexplained sightings were running at about 40 percent. All this was leading inexorably to the following weekend when UFOs were picked up by radar at Washington National Airport in restricted air space over the nation’s capitol, and would become one of the most highly publicized sightings of UFO history. For those reasons, the Nash/Fortenberry sighting received a less than adequate investigation. Project Blue Book quickly determined that the five jets flying out of Langley, AFB could not have possibly been responsible for the sighting, and the case was dropped and filed as an “Unknown.”

It was not until 1962 that the case would be reexamined by the Director of the Harvard College Observatory, astrophysicist Donald H. Menzel, and published in his book, The World of Flying Saucers: A Scientific Examination of a Major Myth of the Space Age (Doubleday, 1963). At the time, Professor Charles A. Maney, a physicist at Defiance College, had been engaged in a rather lengthy correspondence with Menzel, and when the Nash/Fortenberry sighting came up, Maney forwarded copies of the correspondence to Nash, then an advisor to NICAP. This led to a series of lengthy correspondences over a six-month period between Nash and Menzel providing considerable insight into the process by which Menzel arrived at his eventual solution to the inexplicable sighting.

Based on the meager data contained in the official report, Menzel assumed that the sighting could be reasonably explained as a reflection in the cockpit windows, especially considering the nearly instantaneous reversal, which seems to defy the laws of physics pertaining to inertia. In support of this explanation he underscored the apparent failure of the crew and Air Force investigators to make any tests for possible reflections, and generally called into question the credibility of the pilots. In a fairly scathing letter, Nash remonstrated Menzel on this critical point:

“Dr. Menzel, regardless of your figures the western horizon was not quite bright, and regarding your “reflection theory,” in the first place the objects were between us and the West. In the second place, they would have had to be damned persistent, consistent and impossible reflections to have manifested in three cockpit windows in exactly the same way. We first observed them through the front window. As they approached and I moved across the cockpit, I kept my eyes on the objects and saw them through the curved window of the windshield, and we both finished our observations looking through the right side window. That is why there is no evidence (as you complain to Dr. Maney) that the pilots considered that what they saw was a reflection; and you state that we were too excited by what we saw to make the most elementary scientific tests. Again, Doctor, pilots do not excite easily or they would not be airline pilots — please — a little respect for us?”

Dr. Menzel’s next line of inquiry concerned whether the reflection could have been caused by an illumination within the cockpit, or possibly a “hostess taking a drag of a cigarette.” Dr. Maney’s rather sardonic response to this possibility was, “Quite a long drag, wouldn’t you say?” But, nevertheless, the pilots weren’t smoking, the cockpit door was closed, there were no hostesses on the flight and the pilot’s observed the object’s reversal out of the right window below the plane. This pretty well convinced Menzel that an internal reflection was unlikely to explain the phenomenon and what Captain Nash had seen was something outside the plane.

Still, Menzel concluded that Nash’s observations “… are completely consistent with the theory that the discs were immaterial images made of light.”

Therefore, to explain the sighting he theorized that, “…a temperature inversion can lead to a sharp concentration of haze, ice crystals, smoke or other particles in a relatively thin layer. The layer is often invisible until the plane actually goes through it, when it appears as a thin, bright, hazy line that disappears a moment later when the plane breaks through it. Multiple layers of such haze are not unknown, stacked one on top of the other. Now, a sharply focused searchlight, shining at night through a series of such hazy layers, will show up as a series of discs. As the searchlight moves, the discs will appear to spread out, exhibit perspective, and, as the searchlight turns around, the discs will appear to ricochet.”

The soundness of his theory depended on the prevailing weather conditions. Since the official weather reports for that evening indicated that there were no temperature inversions present, Dr. Menzel carefully constructed a scenario in which inversions (albeit in meteorological parlance, a sub refractive condition) could have been present though undetectable by the weather service.

“In the summer of 1952 all the eastern states were suffering from a intense heat wave and drought, and the ground cooled rapidly after sunset, because of the lack of cloud cover during the day. In a period of heat and drought, the nightly cooling produces marked inversions favorable to extreme refraction and reflection. Small in extent, existing only briefly in one place, constantly changing location, such inversions may not be detectable by radiosonde observations.”

Dr. Menzel admitted that his solution does not identify the particular beacon or searchlight responsible for the sightings, though he suggests that, “A light on the Virginia coast, shining northeast toward the plane, could easily have been spread out into a series of images like those observed.” Apparently, the location of the light is assumed to be at the point of the pilot’s initial sighting of the red-glow, beyond and to the East of Newport News. This begs the question why experienced pilots could not identify an apparently fixed high-intensity (red!) light source if it were emanating from a position 25 miles in front and below and directed toward their aircraft. Since the discs were organized in a stepped-up echelon, with the leading disc at the lowest point, one would deduce that the source of the light must have been from behind the aircraft. Had the light source been in front of the aircraft, as Dr. Menzel postulates, the leading disc would have appeared in the highest position in the echelon. Further, a searchlight reflecting off a horizontal cloud layer at an oblique angle to the observer would produce a gradual elongation of the disc as it moves relative to the observer. Nor does the theory account for the two discs that darted out from under the plane and conjoined the original six before disappearing into the night sky. Or the mechanism that would need to be in effect to make the discs appear to flip vertically on edge, reverse position in formation while maintaining relative distances, and then flip back to the horizontal plane (while executing a 150-degree course change at, well, in the words of investigating officer, Major John Sharpe, “…a speed fantastic to contemplate.” Incidentally, 90 miles in 12 seconds equals 27,000 mph!)

In his book, Dr. Menzel asserts that his solution offers, “a highly probable explanation that is consistent with all observations and does not depend on the presence of an extraterrestrial spacecraft.” I have to agree with the later part of the statement, but have no doubt that readers will find further inconsistencies in Dr. Menzel’s impracticable solution.

Some years later, in early 1957, Bill Fortenberry was lost in a Boeing B-377 Stratocruiser crash in the Pacific Ocean, with all onboard. In the early sixties, Captain Nash transferred to Germany, and for the next 15 years flew the Berlin corridors before retiring from Pan American. In a recent interview for the Sign Oral History Project, a still vivacious Captain Nash provided their concluding supposition…

“Looking at the thing shook us up. We stared at each other, and all of a sudden there was this realization that our world is not alone in the universe. Because, nothing could have advanced to that degree of scientific progress without some of the intermediate steps having become public knowledge, or, at least known to the people who were flying. Bill had just come out of the Navy and was fully acquainted with their latest developments. We just knew that they were not from this planet. I know to this day, that it was nothing from this planet.”

References:

Nash, William B. and Fortenberry, William H. “We Flew Above Flying Saucers.” True Magazine, October 1952: p. 65, 110-112.

Ruppelt, Edward J. Report on Unidentified Flying Objects. Doubleday and Company, Garden City, NY, 1956.

Menzel, Donald H. The World of Flying Saucers: A Scientific Examination of a Major Myth of the Space Age. Doubleday and Company, Garden City, NY, 1965.

Hill, Paul R. Unconventional Flying Objects: A Scientific Analysis. Hampton Roads, Charlottesville, VA, 1995.

USAF Project Blue Book files, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C.

Personal files of William B. Nash. (Copies of the Nash files with the Sign Historical Group).

“Rockets, Tracers or Them Devilish Flying Saucers,” Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, July 17, 1952.

The Witness: “A Precise Report on Flying Saucers—Or Something,” Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, July 20, 1952, p. 6.

Nash, William B., 2002. Interviewed by Thomas Tulien and Jan Aldrich, January 4, (Sign Oral History Project).

|

|

|

|