Flight 117 was ninety miles east of Chicago when Captain Robert F. Manning saw the mysterious light.

It was the night of April 27, 1950. The time was 8:25 p. m. Cruising at 2,000 feet, the Trans World Air Lines DC-3 droned westward over Goshen, Indiana. In the left-hand seat, handling the controls, was Captain Robert Adickes, stocky ex-Navy pilot with ten years’ service in TWA. Manning, taller, blond, quiet-voiced, was also a four-stripe captain, but on this particular flight he was in the right-hand seat, serving as first officer, or copilot.

Manning glanced out from the shadowy cockpit. Twenty-five miles ahead. South Bend was a spreading glow in the darkness. Clouds massed at 4,000 feet made a black sky overhead. He looked back to the right to where Elkhart lay some six miles to the north.

It was a familiar routine, picking out Elkhart. He had once lived there and the sight brought pleasant memories.

Suddenly a strange red light moving swiftly near the horizon caught Captain Manning’s eye. It was coming toward the air liner, climbing up on the right, from a point some miles behind.

Puzzled, he watched it close in. This was no wingtip light — the strange red light was too bright. With growing astonishment, he saw that the light was increasing in size. Whatever it was, this was no conventional aircraft.

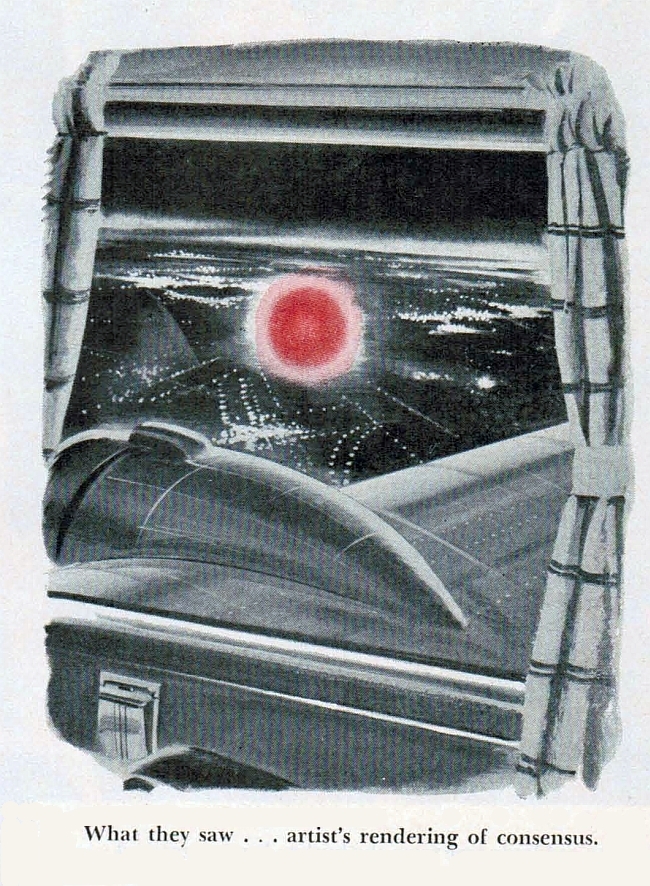

The DC-3 was cruising at 175 miles an hour, but the mysterious glowing object was overtaking it rapidly. It was now an orange-red color, like a round blob of hot metal sweeping through the night sky. Craning his neck, Manning looked down on a spherical shape, glowing brightly on top, the lower part in shadow.

For a second, he half doubted his senses. He had heard Flying Saucer reports from other air-line pilots, but this was almost fantastic. He swung around to Adickes.

“Look over here. What do you make of that?”

Captain Adickes turned. Startled, he raised up and gazed through the starboard window. The thing was still climbing, not quite at the air liner’s level. Over the top, he could see scattered ground lights, and below it, car lights on a highway. He could only guess at its size, but it looked to be at least twenty feet in diameter, probably closer to fifty.

The two pilots stared at each other, then Adickes reached for his mike and called TWA at Chicago.

“We’ve sighted a strange object off the starboard wing,” he swiftly told the dispatcher. “Ask ATC if there’s any traffic near us.”

In a moment, the answer came back. Air Traffic Control had no record of anything near their ship.

Adickes and Manning looked out again at the Saucer. It appeared to be half a mile distant, now keeping pace with the plane. Adickes shook his head incredulously. It looked exactly like a huge round wheel rolling down a road, but how could a thing like that stay in the air?

“I’m going to try to sneak up on it,” he told Manning. He banked the ship gently, but the glowing disk at once slid away, keeping its distance. He tried again, with the same result.

“Call the hostess," he said abruptly. “I want someone else to see this thing.”

Back in the cabin, hostess Gloria Hinshaw caught the hastily flashing signal. She hurried up the aisle and entered the cockpit.

“Take a look out there,” said Adickes, he pointed across the right wing.

The amazed hostess stared out at the glowing Saucer. It was once more flying parallel with the plane.

“What on earth is it?” Gloria Hinshaw exclaimed. “We don’t know,” said Manning.

“Go back and tell the passengers,” Adickes said quickly. “Get them all to look at it.”

The hostess returned to the cabin. The first passenger, in a single seat on the right, was sound asleep. She turned to the two across the aisle — Clifford H. Jenkins and Dean C. Bourland, both Boeing Aircraft men.

“There’s a Flying Saucer out there. Look out the starboard side.”

Jenkins laughed, then he saw the look on her face. He jumped up and peered out the opposite window, Bourland crouching beside him. From the lighted cabin, the shape of the Saucer was less distinct. To Jenkins, it looked like a blur of windows lit with a queer red light. It was unlike anything he’d ever seen — and he knew every type of plane.

While Jenkins and Bourland were gazing at the Saucer, Captain Adickes came hurrying out of the cockpit. The sleeping passenger woke up as Adickes leaned down to look out through his window.

“What’s the matter — what’s going on?” he demanded.

“Look out there,” said Adickes. “See that thing?” He turned to the two Boeing men. “Did you see it? I want plenty of witnesses to this.”

The starboard-side passengers were watching the Saucer, but on the port side aft, the hostess was having trouble. Some of the passengers, including one who had plainly had a drink or two before embarking, thought the whole thing was a gag.

“Sure, let’s all see the Flying Saucer,” chortled the tipsy gentleman. “Let’s see the little men from Mars.”

He stopped, his mouth hanging open, as he saw the strange red object glowing beyond the wing. Pop-eyed, he sagged back in his seat.

When Adickes returned to the cockpit, Manning was putting down his mike.

“I called the South Bend radio range,” said Manning. “I told them to go out and see if they could spot the thing.”

Adickes took the controls, made one more cautious attempt to sneak up on the Saucer. When the thing again slid away, he swung around quickly, to give direct chase.

Instantly, the glowing disk dived. In barely more than a second, it went down to 1,500 feet, racing off to the north past South Bend. Its speed, Adickes estimated, was close to 400 miles per hour. For a few minutes longer, the weird light remained visible — a diminishing bright red spot against the ground. Then it faded and disappeared.

Adickes’ radio flash to Chicago had been picked up by newspapermen. Reporters were waiting at the airport, and the story was soon on the wires. It drew unusual attention. This was not just another Flying Saucer story, to be laughed off. Besides the crew, there were passenger witnesses. Adickes, recalling the ridicule other pilots had met, had carefully seen to that.

Because of the unusual nature of this air-line Saucer sighting, True asked me to carry out a full-scale investigation. Each of the three crew members was interviewed. All but five of the sixteen passengers were located. Detailed eyewitness accounts were obtained by long-distance telephone calls to Seattle, Minneapolis, Chicago, Dayton and several other cities.

As we expected, there were some differences in witnesses stories. All these variations have been noted. The result is this report, which we believe to be an accurate, impartial account of what actually happened on the night of April 27.

Before meeting the two pilots of Flight 117, I talked with others in TWA who knew them.

“Quiet . . . conservative . . . serious . . . careful.” These were some of the terms that were applied to both men. Nobody in TWA questions that Adickes and Manning saw just what they said.

Manning, who saw the Saucer first, has been an Air Force pilot. He has flown six years with the air line; his flight experience totals about 6,000 hours.

By the time I met Manning, at Pittsburgh Airport, there had been several published “explanations” of the South Bend Flying Saucer. One theory was that the red object was simply a reflection of blast furnaces against the clouds.

“Yes, I heard that,” Captain Manning told me. “Also, someone said we’d been looking at a burning barn. Even a first-trip passenger would hardly be fooled that easily — certainly not a pilot with any experience. Adickes and I have both seen ground fires and cloud reflections at night. There wasn’t any similarity. We were ninety miles from the furnaces at Gary, and no reflection or burning barn could climb and maneuver like that.”

“How large do you think it was?” I asked him.

“That’s hard to say, because we could only guess at its distance,” said Manning. “But it had to be fairly large. When I first saw it, the thing was near the horizon. So it had to be several miles away, perhaps ten or more. Even then, it was big enough to stand out.”

Manning quietly spiked the idea that the Saucer had been a jet plane's tail pipe.

“I’ve seen jets at night. If you’re directly behind one, you’ll see a round red spot for a few moments. But this thing was huge in comparison. It didn’t resemble a jet in any way. Besides, I saw it coming up from behind us. A jet’s exhaust would be invisible from that angle. You wouldn’t see much from the side, either.”

When he first saw the object, Manning said, it seemed a brighter color than when it flew alongside. He would venture no opinion, however, when I asked whether this could be interpreted as indicating that it was using less power when it slowed to pace the air liner.

“I can’t swear to its exact shape,” Manning told me. “As it came up from below, it was just a bright red spot at first. Once, I had the feeling of looking down on top of a sphere. But most of the time it was just a large orange-red blob, like a mass of glowing hot metal out there in the sky.”

Although Manning had not seen it as a disk rolling on edge, he admitted that a spherical object could appear like a rolling wheel. He agreed with Captain Adickes’ opinion that the thing had evaded attempts to get closer to it.

“Like flying in formation with another plane,” was his description. “It seemed to slide away when we turned toward it.”

Manning did not speculate as to what the object was, or how it was powered and controlled.

“All I can say is that it definitely was there. Most of the people in the plane saw it. And it was entirely different from any ordinary aircraft — uncanny enough to startle anyone first seeing it.”

Captain Adickes agreed on the bizarre appearance of the thing. When I saw him at Washington, he told me he previously had been only half convinced by other pilots’ reports of Flying Saucers. “But I know now they definitely do exist. This was not an airplane and it wasn’t imagination.”

Adickes said he had seen jet planes at night. He fully confirmed Manning’s rebuttal of this explanation.

“And it wasn’t St. Elmo’s fire or any reflection on clouds,” he added. “A lot of my seventy-eight hundred hours’ flight time was put in on night flying. I’ve seen just about everything you’d expect to encounter, but never anything like that disk.”

Captain Adickes said its proximity had no effect on radio reception. Nor did he notice any deviation on his instruments. The object’s color, he said, was not a bright cherry-red, as some newspapers had stated. Instead, it was about the dull-red color of hot metal.

“Manning and I could only estimate its size,” he said. “It might have been even larger than fifty feet in diameter, depending on its distance from us. This will give you an idea. When I tried to cut in toward it, that last time, it streaked down over South Bend at twice our speed — somewhere between three-fifty and four hundred miles an hour. But even at that speed, it took several minutes to fade out. So it had to be fairly big.”

As it speeded up to escape, Adickes said, it turned so that he caught a glimpse of the thing edge on. It seemed to be about 10 per cent as thick as its diameter.

Other air-line pilots had told him of unsuccessful efforts to close in on Flying Saucers, Captain Adickes told me.

“I thought maybe they imagined it, but now I know better. I tried to sneak up on it, and also to get above it. Each time, it veered away. And when I went straight after it, the thing was off in a flash.”

From the darkened cockpit, hostess Gloria Hinshaw also saw the object veer away. Back in the lighted cabin, she saw it again briefly as it speeded off and dived over South Bend.

“How did it look to you?” I asked her.

“Like a big red wheel rolling along,” she said. “I haven’t any idea what it was, but it was certainly a strange-looking thing. If I hadn’t actually seen it, I don’t think I would believe it.”

None of the passengers was alarmed by the Saucer, but Miss Hinshaw had been worried for a moment when she made the first announcement.

“Some of them got excited,” she said, “but no one seemed to be nervous. And, of course, some didn’t even believe it — they were on the other side, farther back. The rest of us took a lot of kidding from them before we landed. But there’s one thing sure — those who did see it won’t laugh any more at Flying Saucer stories.”

Passenger Samuel N. Miller, manager of the Goodman Jewelry Company in St. Paul, Minnesota, told me the same thing.

“I’d been laughing at the stories since 1947, but not any more. I saw the Saucer, all right — even before the hostess told us.” Miller was on the left side, near the wing. Glancing up from a magazine, he noticed an odd red glow out on the starboard side.

“It was the color of a neon sign,” he described it to me. “I thought at first it was an advertising blimp. Then it got closer and I saw it was disk-shaped. It wasn’t flashing, like a neon sign — it was solid color, just a big red disk.”

Soon after this, the air liner swerved as Captain Adickes made the first attempt to close in.

“It wasn’t abrupt — just an easy turn,” said Miller. “Right after that, the hostess’s signal began to flash, and she ran up the aisle.”

The rest of his story tallied with the crew’s, except for the time estimate. He thought he had watched the Saucer almost fifteen minutes: the pilots’ figure was eight minutes. When I asked him what he thought it was, he admitted he had no answer.

“I can’t believe it’s a secret device of ours,” he said. “They’d be pretty stupid to fly it near air liners, where everybody could see it and talk about it.”

The description given by Clifford H. Jenkins, an engineering supervisor at the Seattle plant of the Boeing Airplane Company, varied considerably from the others. Mr. Jenkins saw the object just over the leading edge of the right wing.

“I’ve never seen anything like it before,” he told me with emphasis. “It was like a row of windows glowing deep red. It had no blinker or clearance lights like a conventional plane.”

“Could you distinguish separate windows?” I asked him.

“No, it looked like windows blended by distance into a solid red band. The thing was perfectly steady, with no oscillation that I could see.”

Just before Captain Adickes came back, Mr. Jenkins said, the plane veered rather sharply to the right, but the angle of the Saucer in relation to the DC-3 did not appear to change. (In effect, this substantiates the pilots’ statements that the object moved simultaneously with the air liner.)

“I had the thing in view three to four minutes,” said Jenkins. “Its top speed was obviously much higher than ours, for it left us behind in a hurry.”

According to Jenkins, the Saucer disappeared on a parallel course.

“The aspect never changed — neither did the angle. The thing just faded in size until it was out of sight in the darkness.”

(Captain Adickes later pointed out that Manning and he had the Saucer in view from the nose of the plane, where it would be visible longer. This might explain Jenkins’ failure to see the object’s change in altitude.)

Since most of the witnesses agreed that the Saucer was round, I asked Jenkins again about its shape.

“It was like a red-hot bar, moving horizontally,” he answered. “If it was a row of windows, then the thing must have been at some distance to blend them together like that.”

(Captain Adickes has suggested that the air liner’s lighted cabin made it difficult to get a clear view, unless the passenger was close to a starboard window. Jenkins and his seatmate, Bourland, were in the aisle, two feet or more from the window. It is possible that this could account for the difference in descriptions: Jenkins might have attempted subconsciously to fit a blurred reddish mass into the conventional pattern of airplane windows. Otherwise, it seems to be one if those puzzling discrepancies often found in group reports of accidents and other exciting incidents. Miller, for instance, was no closer than Jenkins, yet he saw the object clearly as a disk.)

“It definitely wasn’t a hallucination,” Jenkins summed up his opinion, “for at least a dozen people saw it. It wasn’t any known type of aircraft. It couldn’t have been a meteor — it was too slow; besides, it was flying along horizontally.

“It may have been something the United States has developed which it doesn’t choose to announce. Or it may be, as some people believe, that such things come from another planet.”

Jenkins told me that Dean C. Bourland, from Boeing’s Wichita plant, also had seen the mysterious object, but he was not sure whether Bourland’s description agreed with his. I tried to reach Bourland at Wichita, but he was on vacation.

After a little difficulty, I located the passenger who had been asleep in the right front seat. He proved to be Edward J. Fitzgerald, vice-president and sales manager of Metal Parts & Equipment Company, Chicago.

“I missed part of the excitement,” said Mr. Fitzgerald. “I was sound asleep until the pilot woke me up. He was leaning over me, and two men were kneeling in the aisle, staring out the window. The pilot asked me to look out at the Saucer — he said he wanted plenty of witnesses so people wouldn’t think he was crazy.

“When I turned around, I saw this strange red glow on a level with the wing-tip. The effect, after being waked up so suddenly, was naturally startling. The thing looked round, though perhaps not a perfect circle. I estimated it to be about two hundred yards away, but that’s only a guess.

“The pilot started to explain how they’d sighted the thing, then he saw it was pulling ahead. He went back to the cockpit and a second later the plane banked to the right. The ‘saucer,’ or whatever it was, speeded up and then dipped a little. Altogether, I saw it about thirty seconds before it disappeared.”

“Did you see any windows, or any resemblance to a plane?” I asked him.

“No. it wasn’t anything like a plane,” Fitzgerald said positively. “It was a very strange object — almost weird.”

Five officials of the International Harvester Company who were passengers on Flight 117 refused to be interviewed: whether this was to uphold company dignity or through personal preference was not stated. Two of these officials were in the Chicago office — a Mr. Gelzer and a Mr. Irwin. The others were located at the Springfield, Ohio, plant — Mr. Drum, the works manager, Mr. Anderson, the superintendent, and a Mr. Smith, initials unknown.

In spite of their collective refusal, I learned that two or more of this group did see the Flying Saucer. Other witnesses told me of the Harvester men’s comments. One man thought it was round, another oval. Both agreed on its mysterious appearance, its bright-red glow, and its speed.

Another Chicago passenger, Harold C. Weimer, of 5028 Windsor Avenue, reported he did not see the Saucer. He was sitting on the left side, in the rear; by the time he looked out, the object had disappeared. (It was Weimer who suggested the blast-furnace explanation.)

The Saucer was also seen by Martin Nerat, an employe of the Schwerman Trucking Company of Milwaukee. When the hostess made her announcement, Nerat stepped across the aisle and gazed out a starboard window. Like the other witnesses, he was startled by the mysterious object.

When I talked with him, Nerat said the bright-red glow had prevented him from seeing any distinct shape. He agreed with the pilots on the Saucer’s maneuvers.

“Every time the plane turned toward it, the thing pulled away. At the last, it was going a lot faster than we were. I don’t know what it was, but it wasn’t an airplane.”

There were five more passengers aboard Flight 117, but their addresses are unknown. The names are: Bercler, Guttfred, Kehma, Moran, and Moseley. True would appreciate receiving reports from these passengers, so that the record will be complete. Any new information they can contribute will be published in True’s letter section at a later date.

The Flight 117 incident has had an important effect. This carefully noted sighting by TWA pilots and passengers has impressed many Americans. Among those who made public statements after the incident was Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, president of Eastern Air Lines. In a United Press story from Savannah, Georgia, Captain Rickenbacker said, commenting on the Saucers:

“There must be something to them, for too many reliable persons have made reports on them.”

However, Captain Rickenbacker apparently suspected that the Saucers might be American guided missiles. When I interviewed Captain Adickes, I mentioned Rickenbacker’s comment, and I found that he had the same theory.

“I think that the thing was equipped with some sort of repulse radar,” said Adickes, “so it would keep at a certain distance from air liners and other planes.”

The guided-missile explanation is not new, of course. The armed services and the White House have emphatically denied that the Saucers are an American development, but some Americans discount this as a smoke screen to hide a secret weapon.

To recheck, I went to the foremost guided-missile authority in the United States, Captain Delmer S. Fahrney, U.S.N. Captain Fahrney began guided-missile experiments for the Navy in 1936. The television-eye missile was designed and perfected by Fahrney and his engineers. All of the later Army and Air Force developments stem from Captain Fahrney's early work, and the Navy guided-missile program is still far in the lead.

As commanding officer of the Naval Air Guided Missile Test Station at Point Mugu, California, Captain Fahrney exchanges top-secret information with both the other services.

“I can tell you flatly that the Flying Saucers are not guided missiles of the Navy, Army or Air Force,” he said when I interviewed him in Washington. “No guided-missile officer would be stupid enough to test any such device along airways or over cities. It would be criminal negligence — a mechanical failure could endanger lives. Even when launching a missile over the ocean, we clear the test range and keep it patrolled during operations.”

Admiral Calvin Bolster, of the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics, gave me the same personal assurance in regard to U. S. piloted aircraft of advanced design.

“If the Flying Saucers exist,” he said, “they’re not anything we're producing.”

Other high defense officials have pointed out that such top-secret devices, even if piloted, would hardly be tested at random all over the United States, Canada, Mexico and other countries where Saucers frequently have been seen.

The case of Flight 117 is, in chronological order, the ninth air-line Saucer sighting of which True has specific record; a tenth occurred one month later; there have also been, at various times, a number of other cases incompletely documented.

Sightings by experienced transport airmen are impressive testimony to the reality of Flying Saucers.

The Air Force, which undertook the investigation of Saucers, has nevertheless professed to deny their existence from the first reported incident.

On July 4, 1947, shortly after the start of the “Saucer scare,” Captain Emil J. Smith of United Air Lines was still one of the skeptics. But that evening, over Emmett, Idaho, Captain Smith and his copilot, Ralph Stevens, saw nine fast-flying disks above their DC-3. The Air Force’s Project Saucer brushed off the sighting as an illusion.

On July 24, 1948, the pilots of an Eastern Air Lines DC-3, Clarence Chiles and John Whitted, reported seeing a space ship near Montgomery, Alabama. A passenger confirmed that a strange, brilliant object had streaked past the air liner’s window. An hour before, Air Force men at a Macon base had seen the same thing flash overhead, trailing colored flames. After screening 225 plane schedules and finding no craft in the vicinity that could be held to supply the answer, Project Saucer explained it away as a meteor.

Some time after this, the crew of a Pan American Airways plane sighted a strange aerial object between Everett and Bedford, Massachusetts. The pilot and navigator described it as cylindrical in shape, about the length of a P-40 fuselage, and blunt at both ends.

“Weather balloons,” said the Air Force.

Near the end of 1949, a Golden North air freighter was paced between Seattle and Anchorage, Alaska, by a night-flying Saucer. When the pilots tried to close in, the strange craft zoomed at terrific speed. Later, the air-line head reported that Intelligence officers had quizzed the pilots for hours.

“From their questions,” he said, “I could tell they had a good idea of what the Saucers are. One officer admitted they did, but he wouldn’t say any more.”

Early on the day of March 8, 1950, three TWA pilots at Vandalia airport, the municipal field for Dayton, Ohio, were among the many observers of a gleaming object that hovered in the sky at high altitude. They were W. H. Kerr, D. W. Miller, and M. H. Rabeneck. All noted the strange appearance of the object, which, though small to the eye, was presumably huge since it was visible at great height.

Meantime, other observers at Vandalia had phoned Wright Field, headquarters of Project Saucer. Scores of Air Force pilots and ground men watched the disk as four fighter planes raced up in pursuit. The mysterious object streaked vertically upward, hovered for a while miles above the earth, and then disappeared.

Later, Captain Kerr made a report to the Civil Aeronautics Authority. A C.A.A. official said that they already had a full report coming from Vandalia, with affidavits from twenty qualified witnesses.

Captain Rabeneck’s observation, made through binoculars, has a special value. He happens to be an amateur astronomer of considerable experience.

“One thing is certain,” he told Captain N. G. Carper, chairman of the TWA unit of the Air Line Pilots Association. “This was no star, planet, meteor. . . . Not that I believe that any air-line pilot who saw the thing would need an astronomer to tell him that.”

A news story from Wright Field next day said the object had been identified as the planet Venus — although it had been seen in broad daylight, when Venus is practically invisible. When the C.A.A. report reached Washington, I asked to see a copy. I was told it had been rushed to Air Force Intelligence. When I asked the Air Force to let me see it, I was told the report had been sent to Wright Field. Since then, the C.A.A. has officially told me that all such cases reported to them are “in the province of the military” and therefore confidential. I got that answer when I inquired whether the South Bend radio-range operator had seen the Saucer reported by Flight 117. In spite of this, the Air Force still insists that Project Saucer has been disbanded, its investigation ended.

Three days after the Dayton sighting, a similar disk was observed by an American Air Lines group at Monterrey, Mexico. This was on March 12. Captain W. R. Hunt watched the disk through a theodolite at the airport. In addition, the Saucer was seen by forty passengers and the rest of the crew. On March 18, the Air Force again denied the existence of Flying Saucers.

On the night of March 21, the crew of a Chicago & Southern air liner saw a fast-flying disk near Stuttgart, Arkansas. The circular craft, blinking a strange blue-white light, pulled up in an arc at terrific speed. The two pilots said they glimpsed lighted ports on the lower side as the Saucer zoomed above them. The lights had a soft fluorescence, unlike anything they had ever seen.

On April 18, Captain Carl Gray was piloting a Braniff air liner when C.A.A. tower operator at Childress Texas, radioed an urgent message. A mysterious, silvery-white object had been sighted from the tower; the operator asked Gray to be on the lookout for it.

Captain Gray and his crew spotted the thing a few minutes later — a large, round, shining object oscillating at a high altitude. His first thought, that it might be a balloon, quickly gave way to puzzled astonishment.

“I’ve never seen anything like it,” he radioed the tower. Later, two Air National Guard fighter pilots were guided up toward the Saucer by the C.A.A. tower man, who was watching it through binoculars. But the planes failed to reach the object. Its height was later estimated at fifteen miles above the earth. My request for the final C.A.A. report on this sighting was refused, as in the case of the Vandalia affair and, later, Flight 117.

On the night of May 29, 1950, the pilot, first officer, and flight engineer of an American Air Lines DC-6 that had left Washington watched an intensely glowing something approach their plane head on while they climbed southwest-ward a few miles beyond Mount Vernon. Captain Willis Sperry edged right to avoid it, whereupon it swerved left and stopped. When they swung back toward it, the thing resumed motion. As it swiftly circled behind the plane, it passed before the rising full moon in silhouette, and Captain Sperry observed that it was much elongated — “torpedo-shaped,” he called it — and wingless. The lighted portion was at its forward end, and the slim body suggested dark metal. Then it darted out of sight to the east with great speed.

Besides the ten air-line sightings described above, there are incomplete reports of others-a sighting by a Capital Air Lines pilot near Buffalo, New York; a strange encounter on the airway between Alaska and Japan; Flying Saucers reported by air-line pilots flying from Hawaii to the mainland, and other sightings on American domestic lines.

The Air Force either denies knowledge of C.A.A. reports or refuses permission to see them. Concerning its own data, it announces; “There is no investigation going on. Flying Saucers simply don't exist.”

Any thinking person who examines the mass of evidence can reach but one conclusion: the Saucers are real. There remains the debatable question:

What were the objects which all these air-line pilots saw?

As I stated in the January issue of True, there are only two possible answers:

1. Saucers are interplanetary craft. Or,

2. They are extremely high-speed, long-range devices secretly developed here on Earth.

I believe that Admiral Bolster and Captain Fahrney have told the truth. Regardless of any secret weapon's value, I cannot believe that our armed services would risk American lives by testing it above populated areas. In addition, the incredible range and speed of the Saucers and the worldwide spread of sightings exclude the man-made weapon theory.

Perhaps the following quotation from a formerly secret Project Saucer report is the key to the mystery. Discussing the motives of possible visitors from space, this official Air Force statement says:

“Such a civilization might observe that on Earth we now have atomic bombs and are fast developing rockets. In view of the past history of mankind, they should be alarmed. We should therefore expect at this time above all to behold such visitations.

“Since the acts of mankind most easily observed from a distance are A-bomb explosions, we should expect some relation to obtain between the time of the A-bomb explosions, the time at which the space ships are seen, and the time required for such ships to arrive from and return to home base.”

Was the release of this Project Saucer report a blundering slip-up? Or was it part of a slow, halting program to prepare us for a dramatic disclosure?

After a year's investigation, I believe that Air Force denials and contradictions have been due to fear of public reaction. I believe that Project Saucer was created to cover up the facts until the American people could be prepared. Apparently, there are some men in the Air Force who still think we are not ready.

For almost three years, the answer to the Flying Saucer mystery has been a cautiously hidden secret. If we are not ready now, we never shall be.

It is high time that the American people were trusted with the truth.

— Donald E. Keyhoe

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|